.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

It's cold. I know, I know. It's winter, you say. It's supposed to be cold. But this polar vortex came sweeping down and plunged us into a deep freeze. Nights with temperatures in the single digits (and remember, I'm talking about Fahrenheit temperatures here.) Daytimes that never reach the freezing point. So yes, I really mean it when I say it is cold.

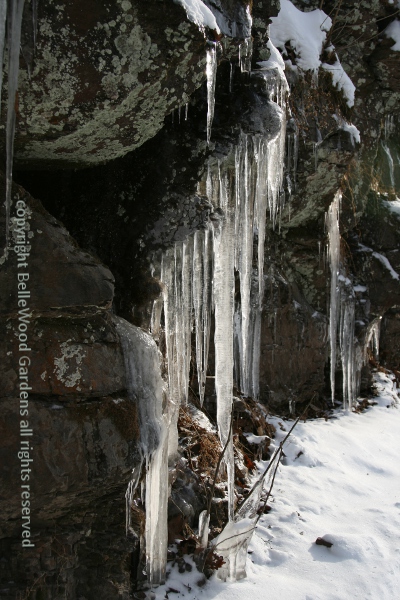

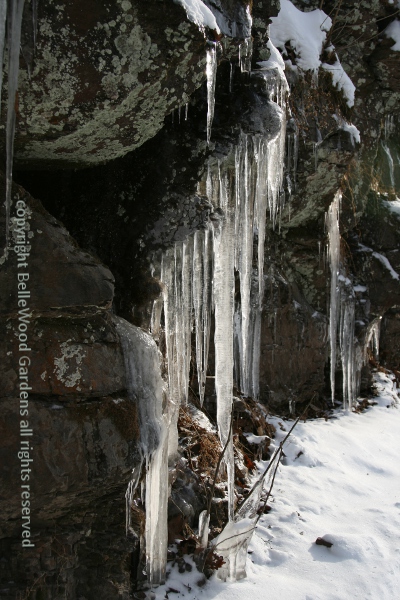

There are icicles emerging from the rocks along Creek Road, where ground water seeps through the cracks and crevices, dribbles out and then solidifies.

The Delaware River is icing over. Pads of ice are sluggishly moving downstream. Where they swirl against the river banks they lock together, creating solidifying icy ridges.

Most of us have little to do with ice. Cubes to chill summer drinks, crushed ice for picnic coolers, a supermarket or fish store's display of sea food on a bed of crushed ice. Ice comes in bags at a convenience store, or automatically plopping into a bin hidden in a refrigerator's freezer compartment. Anyone out there reading this, who remembers when (and why) we called them an "icebox"? Why do you suppose that was . . . . It was because perishable food was kept cold through the use of very large blocks of ice in an upright insulated refrigerator-shaped box. When I was a little girl my aunt had a summer cottage with an icebox. The ice man delivered three days a week. And if I was polite he'd chip off a chunk of ice for me to lick and nibble and play with. The ice he sold was probably manufactured. But once upon a time ice would have been most commonly available as a natural product.

And that meant harvesting the ice in winter. "In the old days," Reinhold (a trustee at the Howell Living History Farm in Mercer County, New Jersey) mentioned to me, "ice harvesting was a "no cost crop" meaning you did not have to spend anything to harvest the ice. So after warm winters when no ice could be harvested, it got costly for the farmers when they had to purchase ice for their ice box in the summer."

Today they're harvesting ice at the Howell Living History Farm, from the pond behind the farmhouse. It was rather touch and go if they could do it. We'd had a spell of milder weather after the first cold weather. The ice must be a minimum of 4 inches thick before people can walk out on it. And the spring that feeds the pond means that the water is coming up from the earth somewhere around 55 degrees Fahrenheit. (You've heard about geothermal heating / cooling systems, haven't you?) So really cold weather is necessary for the confluence of conditions that will allow the harvesting of ice.

Freshly harvested ice. Bet you never saw that at a farmer's market!

Notice the layers of clear ice / cloudy ice. The cloudy layer is ice that formed from a layer of snow. The clear ice is pond ice. It's a better quality for storage.

Even though it is very cold there's a good turnout of interested people, adults and children.

Here's how the ice is harvested.

First, the ice is scored to mark the cut lines. The scoring of the ice before the cutting helps the farmer to get the exact size to fill the icehouse efficiently without having to cut a block in half or make other adjustments.

Next, the ice is cut with a coarse-toothed saw into large, discrete blocks.

Ice floats (you know that!) so the blocks remain on the surface.

Then someone with a hooked gaff yanks each block up onto the ice.

Fine. It's winter. We have ice. It's naturally cold at this time of year.

How do we keep ice for use when it's no longer cold? Why, in an icehouse.

An icehouse is an ingenious low tech means of keeping frozen water from rapidly melting away in warmer weather. A deep pit is dug in a shady site. Reinhold told me that "Our icehouse is a 50:50 icehouse. Meaning 50% above and 50% below ground. The further south you go, the more of the old icehouses are below ground. At Howell Living History Farm we only lose about 30% of the ice per year in the icehouse, even during a hot summer. So if we have enough ice in there, it would stay up to three years. We use sawdust as insulation and separation between the blocks of ice. If there would not be any sawdust between the ice, we would end up with a single gigantic block of ice in the icehouse (which would not be a good thing.) Since the farm had access to the icehouse, social events like valley picnic or some sort of ice cream party were held at the farm. "

But first the ice must be moved from pond to icehouse.

A gaff is used to push a block of ice across the pond, so easy that small children were doing it. Next, two at a time, blocks of ice are edged up onto a wooden ramp. A two-pronged hook is set at the lowest edge. Then someone up by the icehouse pulls on the rope fed through a pulley (mechanical advantage with a pulley is a good thing) that guides the cakes of ice up to the top.

One at a time, each cake of ice slides down a ramp into the pit at the bottom of the icehouse

where someone is waiting to fit it into place like a very cold mosaic.

It will take many cakes of ice to fill the pit. Ice will continue to form - at this time of year, with continuing cold weather, water-into-ice is a renewable resource. It's ice in summer that's unique, something all to easy to forget in modern times where the year-round availability of ice is taken for granted.

Accompanied by the jingle of sleighbells, their breath steaming in the cold air,

a team of draft horses pull a sledge across the snow-covered field.

Back to Top

Back to January 2014