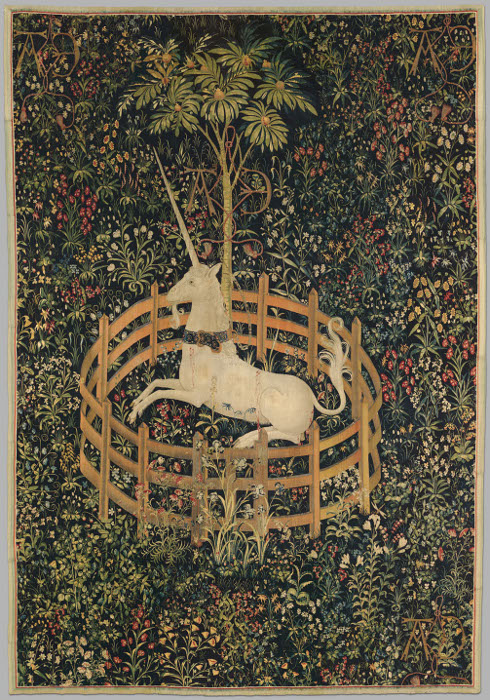

image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Unicorn In Captivity

.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

A visit to The Cloisters offers its visitors a step back into medieval history. For gardeners, there are the four cloister gardens. Saint Guilhem Cloister has potted plants. Of the three planted cloister gardens dating to the Romanesque and Gothic periods, Trie Cloister is currently undergoing renovations. When completed it will have a flowery mead of chanson and romance. Cuxa Cloister features both period and contemporary perennials. Though not modeled after a specific historical cloister garden, it is the Bonnefont Cloister which most closely approximates a medieval herb garden with raised beds bordered by bricks and wattle fences, fruit trees and flowering plants. All of its plants are species documented in medieval sources: in medieval treatises and poetry, garden documents and herbals, and medieval works of art such as stained-glass windows and column capitals. And tapestries.

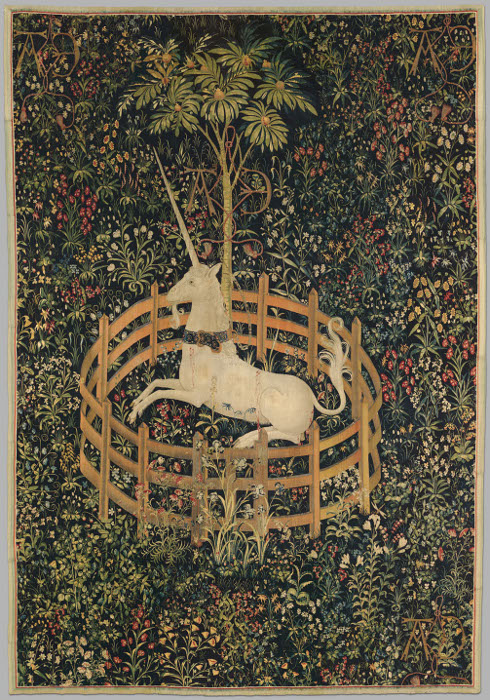

image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Unicorn In Captivity

Most renown and beloved are the seven tapestries of the Hunt of the Unicorn dating from between 1495 and 1505, which show a group of noblemen and hunters in pursuit of a unicorn. The tapestries are huge. For example, the Unicorn in Captivity tapestry shown above is 12 ft. 1 in. x 8 ft. 3 in. Woven with a wool warp and wool, silk, silver, and gilt wefts, colors still vibrant today were produced with vegetable dyes: yellow from weld, red from madder, and blue from woad. The background is woven in the millefleurs, thousand flowers design style, referring to a background made of many small flowers and plants. Their depiction is quite accurate. I could recognize not just the pomegranate tree but also narcissus, dianthus, Vinca minor or running myrtle, violets, Lilium candidum or Madonna lily, forget-me-nots, and strawberries. There are actually 101 plants depicted in the tapestries, eighty-five of which were identified by two botanists, E. J. Alexander and C. H. Woodward, in an article first published in the May 1941 issue of The Journal of the New York Botanical Garden.

A medieval garden was planted for all five senses: sight, taste, touch, fragrance, and sound. With more than 250 species of herbs, the Bonnefont garden is colorful. Brush against a rosemary or lavender plant for fragrance. Nibble a leaf of mint to taste its refreshing flavor. Pause, and listen to the wind scattering autumn leaves, skittering across the pavement. But the primary reason for cultivating the great diversity of plants was a practical one. Their beauty might be a benefit, but secondary. These plants were the source for medicine to treat disease and wounds, dyes for tapestries ( illuminated manuscripts and painting generally used earth pigments and ground up minerals), seasoning for food and drink.

Plants are grouped in beds according to their general use: culinary, aromatic, magical, medicinal, and art. Of particular interest are the plants used by medieval artists, including those providing pigments for manuscript painting and textile dyeing.

Bearded iris, Iris germanica, is a popular garden plant, today for its flowers in a rainbow of colors, historically for its craft uses. According to Franco Brunello in his 1973 Dyes and Dyeing, "The blue perianth of its fine inflorescence, when squashed, pulped and mixed with lime or other alkaline substances, gives a fine green color called Iris Green once used in watercolor painting and sometimes for dyeing." The trimmed back leaves and swollen tubers of these recently divided plants are indication of the ongoing care provided by the cloister's gardeners.

"What's this?" I had to ask. I know of madder, Rubia tinctoria, and that its roots are source of a good red dye (called rose madder or Turkey red) but cannot remember ever previously seeing it in growth. Little hook-like growths allow it to cling and climb up this wattle trellis. Apparently in medieval times madder was also a medicinal plant, its roots used for treating a variety of urinary problems such as kidney and bladder issues, and also externally for wounds and bruises.

There was an interesting talk about beer and ale making, presented as we stood by the planting bed where luxuriant hop vines, supported on sturdy ropes, go soaring to the roof tiles. They grow both the German Hallertau and varieties of wild hops.

.

Carol (that's she in the center of the group, just by the wall's massive buttress) is this afternoon's presenter of an interesting talk about the cloister's plants. As well as edible, medicinal, craft uses and other practicalities she explained the period's theories about bodily humours - wet / dry, warm / cold - and the matching attributes of different plants. Patient with questions, she guided our group from quadrant to quadrant, explaining the plants and their uses, and often with an amusing tidbit of information. Two espalier pear trees at the wall - the massive one to the left was planted in 1938 when The Cloisters opened.

Here's a better look at the younger espalier pear tree.

The trees that especially fascinated me are the quinces, one to each quadrant. Planted the year The Cloisters was opened, the four quince trees are now 75 years old. It's rare to see quinces in a grocery store these days, and they are pricier than apples and pears should you find them. Why am I so enamored of these deliciously aromatic, too-hard-to-eat-raw fruits? They make the most marvellous preserves, cooking into a Venetian red, delectable treat. In fact, quinces are the original preserves. Named coing and cotignac in France, the fruit is called marmello in Portugal, from whence marmalade gained its name. It would be served at the end of a meal, as a digestif.

Such beautiful quinces. I do most earnestly hope someone is allowed to take them home to cook with them so they do not go to waste. Preserves, a quince fool for dessert, quail or pheasant with quince, a quince and pear tart - so many possibilities.

Probably more familiar is the herb sage, Salvia officinalis. Culinary, medicinal, sacred.

Cardoon is related to artichokes. Beautiful jagged, silvery leaves make a magnificent accent in the garden. It is, alas, not quite hardy over winter, at least not in my New Jersey garden. I sometimes see the broad midribs for sale in the produce section of the supermarket. Prickly, cardoons take some advance preparation and are likely to stain your fingers brown when you pare them before cooking.

Tansy, Tanacetum vulgare is another herb with several medieval uses. It was a popular strewing herb, tossed among the floor rushes both for its scent and - more importantly - its disinfecting properties. It's also an insect repellent, so that would have been a useful aspect too. A bitter herb, its flavor is rather strong for modern tastes. And the herb's medicinal properties range from vermifuge, general tonic, treat gout, and more. What a handsome willow withe support keeps it growing in an orderly manner rather than sprawling about.

The wattle supports and quadrant edgings (you can see a piece of one in the quince tree image) are of the period and quite handsome. They're bought in, not made here at The Cloisters. I didn't think to ask how long they last, a few years I expect.

A magnificently sculpted well head is centered on the crossing paths that define the four planting beds. Carved of Istrian limestone early in the fifteenth century, the relatively soft material shows deep grooves in the rim where ropes used to pull up water buckets, again and again and again, wore down the stone.

Gardens need tending. There's digging and planting, weeding and watering. And harvesting. A small cubbyhole of a room to the right of the espalier pear trees had some bunches of herbs hanging to dry from a raised ladderlike device pulled up near the ceiling. Jars of seeds on a shelf. A couple of straw bee skeps are on display. These two riddles, for sifting soil, a watering can and a bunch of flowers make a pleasing still life.

After more than five hours I've seen - and heard - so much. There's more that I know should get another, deeper look, and others that I have not even noticed. Clearly I took far to long to make my first visit to The Cloisters. The next one, however, will come much sooner. Time to find my car and head home, my mind filled with beautiful memories.

Back to Top

Back to October 2013