I've never seen any reason to stop with a visit to one garden if it's possible to visit a second one on the same outing. Especially with gasoline prices what they are. I made the mistake of calculating what it costs me for the round trip drive from home to these gardens, and am now doing my best to forget. But here I had a beautiful day with pleasant company accompanying me, time in hand with no urgent demands to send me quickly scurrying homeward, and Wave Hill beckoning like a lodestone. So that's where we went for lunch and a stroll around the grounds.

And then on the way home Doug and Susan asked if I would like to stop at Honey Pot Hill Orchards in Stow. Of course I said yes. A busy place with grownups and children busily buying apples and pears, cider donuts, feeding animals, wandering around.

I drove to Trenton, New Jersey yesterday, parked my car and got on Amtrak for a leisurely 5 plus hour ride to Massachusetts. Comfortable seats, charming views out the window of cities, backyards, and coastal marshes. Then today my host and hostess brought me to Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston. My topic, "Into the Woods: Companion Plants for the Rhododendron Garden" was the Brooks Lecture presentation for of the Massachusetts Chapter of the American Rhododendron Society at their Founders Brunch. A pleasant occasion for all concerned, myself as well as my audience. And afterwards, well afterwards I had a pleasant stroll on a sunny November afternoon around the grounds of Tower Hill.

Taxonomy. If there is anything that intimidates a gardener, taxonomy ranks near the top of the list. Yet where would we be, without a system that places plants in a hierarchy of relationships. No doubt, even more confused. My husband has a very basic system for classifying plants. Either they are grass, or they are not-grass. And the way you tell the difference? You cannot cut grass with a chainsaw. That means that daffodils and dahlias, cannas and chrysanthemums, even bananas, all fall into the grass category.

There once was a system not so far different from his. Around 300 B.C. the Greek botanist Theophrastus divided plants into four groups: trees, bushes, small shrubs, and herbs. A later system, that of the Greek doctor Dioscorides, in 77 A.D., classified plants by their usefulness, vegetables, medicinal and aromatic plants, for example. Dioscorides' system was used in books about herbs until the 16th century. Around then, the number of known plants became large enough that such systems did not work.

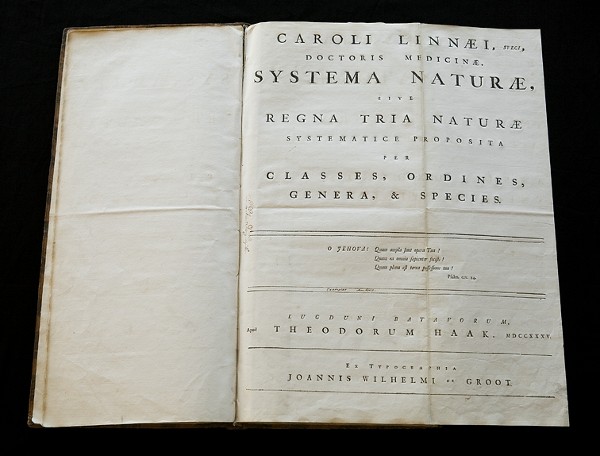

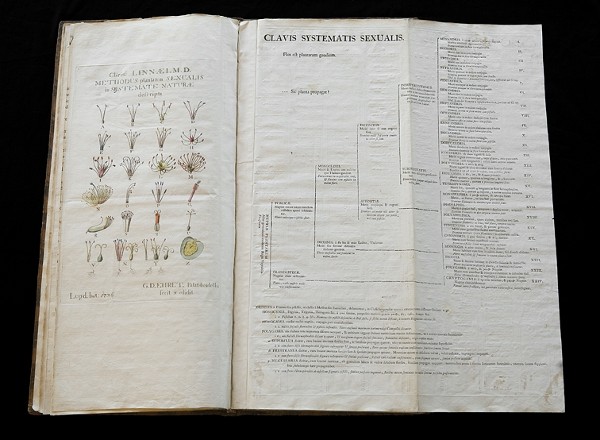

It was in 1735 that Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish doctor and naturalist then working in the Netherlands, published a slim little 11-page book that classified plants based on their sexual parts, particularly the number and arrangement of the stamens, their male parts. Subsequent editions expanded, enlarged, and expounded on his theory. Using the 24 classes he described it became much easier to classify newly discovered plants. By the time he was done, Linnaeus had described and classified 7,700 species of plants. He named 4,400 species of animals. In addition to developing this universally applicable system, Linnaeus also created binomial nomenclature. Current research utilizing DNA to explore plant identities may be changing some of our understanding of their relationships. Linnaeus remains the man who introduced to biology a classification system for all living things. Dr. Robbin Moran, Curator at The New York Botanical Garden notes that "Linnaeus' penchant for naming and describing the living world led to his being called the "second Adam," alluding to the biblical Adam who named all living things in the Garden of Eden."

In celebration of the tercentenary of Linnaeus' birth in 1707, his personal copy of the Systema Naturae is on a world-wide tour. Organized in close collaboration with the Consulate General of Sweden in New York, and the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm where the book is housed, it was here in the United States for a week in early November. And three of those days, November 8th through 10th, were at The New York Botanical Garden.

As well, the LuEsther T. Mertz Library had several works from the collections in the display case of the rare book room. The Hortus Cliffortianus of 1737. George Clifford, an Anglo-Dutch merchant and director of the Dutch East Indies Company had what must have been a wonderful garden at Hartecamp, near Haarlem. From 1735 to 1737 he employed Linnaeus as physician and horticulturist. Linnaeus book describes and classifies the plants in Clifford's garden. It is a precursor to the Species Plantarum, a copy of which, published in Stockholm in 1753, was also on display. It was in Clifford's house that Ehret and Linnaeus met. The Species Plantarum has been the starting point for all modern botanical nomenclature since 1905. A copy of Robert John Thornton's "New Illustrations of the Sexual System of Carl Linnaeus" (more frequently known as "The Temple of Flora") published in 1807.

And two little books that very much appealed to me. In 1732, while in his mid-twenties Linnaeus received a small grant to explore and botanize in the remote region of Lapland. His "Flora Lapponica" was published in 1737. I'm sure it was while he was that that he became fond of the plant said to be his favorite and that was to be named for him, Linnaea borealis, or twinflower. When he was raised to the Swedish nobility in 1757, he took twinflower as his own personal symbol. And displayed next to it was Lachesis Lapponica, a posthumously published memoir of his travels in Lapland published in 1811, in English, by J. E. Smith, president of the Linnaean Society.

.

Periodically throughout the year The New York Botanical Garden offers special Plant Lovers Saturday programs with three concurrent sessions offering students their choice of a couple of topics in each time slot. Today was Japanese Gardening Saturday. A topic in harmony with Kiku: The Art of the Japanese Chrysanthemum and the exhibit of Plants of Japan in Illustrated Books and Prints in the William D. Rondina and Giovanni Foroni LoFaro Gallery of the LuEsther T. Mertz Library.

I was teaching in two sessions:plants from Japan for American Gardens in the morning. There are plants from Japan that are ubiquitous in our gardens, everything from Japanese pachysandra, Pachysandra terminalis, rather than our native Allegheny spurge, P. procumbens. Japanese azaleas, Japanese maples, Japanese flowering cherries, Japanese painted fern - the list goes on and on: hostas, daylilies, bleedingheart and more. As well as familiar plants, I was interested in sharing with students some less common plants that they might want to seek out and grow, such as several species of Japanese jack-in-the-pulpit to woodland primroses, and some real rarities like shade-tolerant Deinanthe bifida with its summertime flowers reminiscent of individual hydrangea florets.

And in the afternoon my subject was elements of a Japanese-inspired garden. As I reminded students, a pine tree plus a rock and a Japanese stone lantern do not a Japanese garden make. Nor is the a single archetypical "Japanese garden." Do you refer to a hill-and-pond stroll garden, a dry Zen garden, or something else entirely? What we can take from a study of the elements and the different garden styles is inspiration to enhance our own gardens. The use of stone as an element of garden design, fences and water features, and paths.

Lecture, discussion, and slides are all important elements of a well-taught class. There is, however, something about hands-on that conveys information in a way that stays with the students. So today we made a path.

As I left the water lily courtyards I decided to take another look at the bonsai. Only to find that they are no longer there. An organized frenzy of building is underway. The garden railroads are back in town.

One holiday season a friend of mine bought herself a set of Lionel trains, and a circular track to go around the Christmas tree. As a child she'd always been jealous of the time her brother was given just such a train set, which quickly became a family tradition. The New York Botanical Gardens has just such a tradition, but on a grandiose scale. The earliest memory I have of the garden railroad exhibition goes back to 1992, when the first exhibition was staged. The trains ran past buildings that were houses for the fairies who live in the bottom of the garden, roofed with moss-covered bark slabs, walls shingled with oak leaves, windows framed with cherry bark shutters. All of the houses and bridges were made from natural materials: branches and vines, bark and leaves, seeds and pods and pinecones.

The next winter, 1993 / 94, the Enid Haupt Conservatory was undergoing renovations. So the holiday train show moved outdoors, to the sweep of lawn near the Beaux Arts museum building. I remember my breath steaming in the chilly air as trains chugged through a snowy landscape, past buildings dusted with white, and the waterfall had icicles forming at the edges where water splashed and froze.

.

.

November. We've fallen back from daylight saving time (though what we saved I'm not really sure.) Leaves are dropping, dropping from the trees. There's been a kiss of frost that's withered tender plants,

I wanted yet another visit, solo this time, to saunter slowly and enjoy Kiku, The Art of the Japanese Chrysanthemum at The New York Botanical Garden at my own pace rather than with a group while conducting a tour ( go to October 2007 diary entry and scroll down to Kiku at the New York Botanical Garden.) Mind you, the tour was fun. I liked the energizing feed-back of everyone's pleasure with the setting, the kiku, and (or so I'd like to think) my presentation.

Overnight rain. The overcast morning skies did not deter me and I left midmorning. Happily, the afternoon brought scattered clouds and sunshine. As I walked through the Conservatory doors and out onto the plaza, chilly autumnal breezes caught the thinly sliced bamboo canes of Tetsunori Kawana's sculpture and set them dancing around the massive yet also airy intertwined framework. It's a favorite place for visitors to photograph each other. Birds are attracted to the structure, darting into the upper portion, then flitting out again.

.

It's time, past time, to button up the greenhouse for winter. With my usual marvellous sense of procrastination I put everything off until frost was imminent. Then, having hauled all "at risk" plants indoors, that's when I started cleaning up, tidying things, and doing what could have / should have been done over the summer or earlier in the fall. One major task - I decided it was time to change the bubblewrap insulation that cuts my winter heating costs. That involves stripping off the old stuff (easy enough), washing the glass (simple, but complicated by the massive plant bench against the south wall), stripping off the old double-sided sticky tape on the vertical framing members of each 2-foot wide glazing unit and replacing it. Then install new bubblewrap.

I ordered a single 80-foot roll of 2-foot wide greenhouse insulation bubblewrap and two rolls of the sticky tape from Charley's Greenhouse & Garden, from whom I bought my greenhouse lo these many years ago. That's just enough bubblewrap for my 8-ft X 18-ft lean-to greenhouse, less the area of clear glass for viewing from the kitchen, which I close with a night curtain. The greenhouse bubblewrap is not the same as the packaging version. Holds up better to sunlight.

I love my greenhouse. I love it even more in winter, when there's snow outside and all the "housekeeping" - setup and repotting of winter-flowering lachenalia, freesias, veltheimia, and more, is all accomplished. And I can walk through the garage with my morning coffee, open the greenhouse door and enter a world of green and growing plants without leaving home.

we reached the New York Botanical Garden a few minutes before the 10:00 a.m. opening

that leads to the Conservatory entrance and in to the holiday train show.

We strolled along the broad walkway that parallels the perennial garden,

admiring the benches now decorated with evergreen boughs and pinecones,

embellished with bright red bows.

I can imagine the boxwood hedges limned with a dusting of snow.

and the Children's Adventure Garden will be ahead on our right.

and this is the one that appealed to me the most. Just charming.

holding ginger root and rolling pins, looked somewhat tired from their labors.

I think they needed new moss to refresh their people-size figures.

as they humped their pinecone-covered bodies across the plaza.

garden railroads at the New York Botanical Garden.

And the holiday train show at the New York Botanical Garden has become one of the traditions

Grownups in pairs and trios, grandparents with grandchildren, and

groups of school children were here to enjoy the train show too.

and keep an eye on things, gardeners for landscape maintenance,

here busy at work "mowing" the grass.

Spartan and Grimes Golden, and crab apples for making jelly.

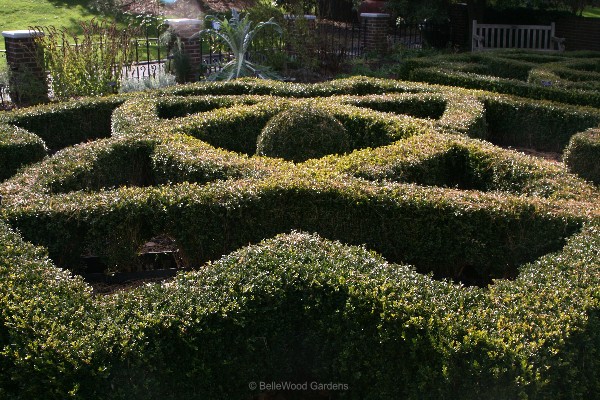

It is said to be a replica of the famous Hampton Court maze in England. Neatly clipped

evergreen walls are quite different from the more familiar cornfield mazes that yearly change

their layout This one is more substantial, its form more fixed in time and space.

But time constraints suggested just a look, not a stroll into green-walled mystery maze.

Next time . . .

Si Caelum in Terra Sit Haec Id Est Laetitia Aeterna.

Which means, (or so I've been told), "If Heaven were on Earth, it would be eternal Joy."

Begin with just a step outside the Stoddard Education and Visitors Center,

across a path, and an allée of oaks invites you for a stroll.

crab apples bedecked with golden fruit, or sparkling with ruby red.

when winter's snow and ice locks much else away from reach.

It won't take much to coax me back to Tower Hill.

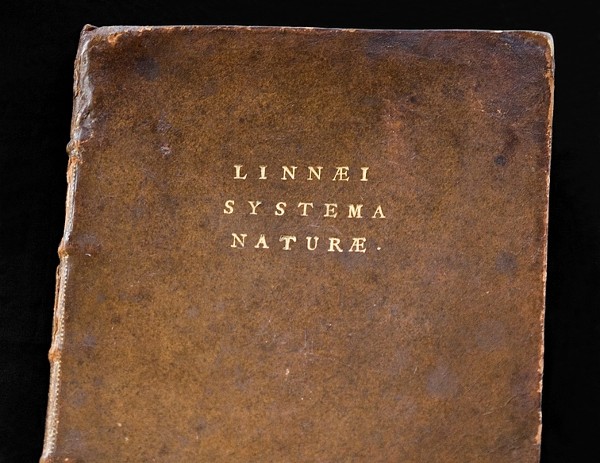

Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Stockholm

Carl Linnaeus' personal copy of Systema Naturae

Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Stockholm

Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Stockholm

Systematis Sexualis pertaining to plants. It is to this page

that the book is opened in its display case.

but also several holes in its bowl.

formal rectangles, irregular field stones,

even smaller than hand-sized cobbles.

Then sponge painted them in the red hue

of New Jersey shale and slate.

and spread the paving stones across the floor.

As students cooperatively worked on their path

I provided a modicum of commentary, pointing out

what worked, what almost worked, and where

improvement was needed. One student commented,

"This is harder than it looks!"

Photograph Credit Ed Impara 2007. All rights reserved.

to walk the path, to see where their footsteps naturally fall -

on a stone, at an edge, off the path. Indeed, this is harder than it looks.

a better understanding of Japanese design concepts, and that will

enable them to give a Japanese flair to their own, American, gardens.

and the buildings, get the trains running, tuck in hundreds of plants, place the lights . . .

and then step back and look at the magical results.

in the large pool of dark water that's the first thing you'll see upon entering the conservatory.

the Statue of Liberty, Rockerfeller Center, Enid Haupt conservatory, Empire State Building, the Little Red Lighthouse,

a towering Brooklyn Bridge 28 feet long and 14 feet high, and - like the other structures - built out of natural materials.

for those who, like me, travel from west of the Hudson River.

of reality, while also bringing a magician's touch of fantasy into play. Structures from previous years, others

that are new this year. And ideas for the future spinning from his imagination, to be applied to garden railroads.

Hours are 10:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday, with an early, 3:00 p.m. closing on Christmas Eve,

and closed on Thanksgiving and Christmas Day, and most Monday. however it will be open on Monday, December 31.

Saturdays in December, plus the holiday week ending with New Year's Evening the Garden will remain open until 9:00 p.m. .

Those dates are November 23 and 24 and December 1, 8, 15, 22, and December 26 through 31.

of timed tickets, which are already available online. You might want to order tickets now.

present as magnificent a display as was seen in the first two weeks.

Relatively speaking, these kengai are somewhat simple to exchange.

A different matter for the ozukuri and ogiku.

Last year, in 2006, two more were grown. This time they were placed on public view.

And for this exhibition Yukie started training plants in November 2006, (see here)

Yukie trained more than the actual numbers needed for display. For ozukuri there would be

three plants displayed in their pavilion, the second set for the change-over midway through the exhibition,

plus two in the conservatory and also "understudy" plants, held in reserve in case of need.

Once at the pavilion each flower must be delicately adjusted to exact relationship with the others for perfect alignment.

The metal support to which each stem is tied can be adjusted - a little up, a little down, a little angled.

It takes two people, one looking and one tweaking. Each and every flower gets a supporting collar.

There are extra flowers - can you see the one sort of laying down in the lower picture.

They are living reserves against the emergency of a broken stem or damaged flower.

Yukie will come and take the responsibility of cutting out the now-unneeded extras.

now each ogiku is carried, one by one, to their display pavilion. They must be untied from their stakes,

and ever so carefully manuvered under the wooden bar and into the below grade pit that's been dug

to receive all the pots. Each is then re-staked and re-tied into place. Then the careful, fussy work

of lining up all the plants in three dimensions: front to back, side to side, and also the flowers' plane.

A single sheet of paper would rest atop the flowers with no gaps, no high spots. Just perfection.

placed to graduate in height from back to front. The plants are tagged for their place in line: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

There is a simple wooden framework to provide the correct geometry, front and back straight and parallel.

A metal slat close to ground level for the angle of each row, matching the adjacent row, again and again.

from teaching a class at Rutgers Gardens in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

(Today's class was about Winter Interest in the Garden.)

Today, in amongst the chanterelles and other mushrooms

they had a few truffles, priced at a modest $299 per pound.

(I've seen them at $899 / pound, three times that sum.)

Like mushrooms, truffles don't weigh very much. Checking to see

which of the smaller ones was most aromatic, I chose a less-than-walnut

size truffle that priced out at just under $9. That is an affordable indulgence.

Chose seven, tucked them - still in their shells and surrounding the truffle -

in a bowl. In the morning I microplaned half the truffle into fine shreds.

Beat together the now shell-less eggs and shaved truffle shreds together

with two tablespoons of whole milk. And cooked them in a double boiler over simmering water.

with thin shavings of the remaining piece of truffle.

and sauteed them in a cast iron frying pan with chopped onion,

and some chanterelles I'd picked here on Creek Road and frozen.

turned up a bottle of Louis Roederer Brut Premier Champagne. Though not vintage,

I thought it too good to mix with orange juice. So we drank it straight.

by the cook, her spouse, and their house guest.

Yes, I like the view without the diffusing effect of the bubblewrap. But the heat loss

is uneconomic. I only keep my greenhouse heated to 50° Fahrenheit, but even so.

The glass is single pane tempered glass and when nighttime temperatures decline

into the teens and single digits one might just as well have open windows in their stead.

One actually laid her egg mass inside, and they hatched that winter. Cannibals

at the best of times, there were a few aphids but not much else for the hatchlings

to dine on but each other. Notice those blobby jellyfish-looking circles?

They're the remnants of the bubblewrap bubbles that fragmented when I peeled it off.

Photograph Credit Paul Glattstein 2007. All rights reserved.

Hose it off to get the film of dirt nice and wet. Wrap a towel around the gizmo for scrapping snow

off the garage roof. Two rubber bands hold the towel in place. Wet towel.

Squeeze a line of dish detergent on the towel. Squeegee. Hose off again. Water play.

Photograph Credit Paul Glattstein 2007. All rights reserved.