Why do you think it is called "handicraft"? Because handy items are created? Because it is the work of hands? No idea. But I do know that knitting is a handicraft that draws us together. My daughter has her Stitch Sisters, my sister has her Knit and Nosh group. Me, I'm one of the Wednesday morning group of irregulars that meet at the Bridge Cafe in Frenchtown for camaraderie, conversation, coffee, and - what else - knitting. In our group (see my hand go up) are the veriest beginner. At the other end of our rainbow spectrum is one woman who used to have a knitting shop, who creates patterns for magnificent sweaters, said patterns commercially printed and offered for sale in knitting shops.

I've seen socks "on the needles" and then on the feet, so magnificent I'd never cover them up with shoes. Baby hats, felted projects, all sorts of items created with - reduced to an absurd minimum - two sticks and some woolly string. I've seen all sorts of "sticks" - made of metal, plastic, wood, used two at a time, three at a time, or essentially one formed as two tips with a flexible middle.

There's always generous help with dropped stitches and more complex quandaries. Laughter, happiness, and knitting.

Jerry was having a significant birthday. It would be a quiet celebration at home. With a very snazzy cake. Now, not everyone has a patissiere fly over from Paris to bake their birthday cake. In this case, daughter Dot flew in to bake his cake.

A red velvet cake. She e-mailed the New York Times recipe, its list of ingredients, and the necessary number and size of cake pans for Bea and Jerry to have on hand for the event. Considering that she'd be flying in the night before, all Dot wanted was to just make the cake, not have to shop for it too. Now, a red velvet cake is red thanks to food dye. Lots of red food dye. As a matter of fact, 3 ounces of the stuff. Searching for the colorant (it not being something they ordinarily use) Bea and Jerry asked a store clerk where it would be shelved. Along with mentioning the the correct aisle, he suggested that they could just as easily buy red velvet cake mix. Guess what - that's what they did.

The cake baked up just fine, all three layers. The frosting was a lavish, unctuous blend of whipped cream, cream cheese, and mascarpone cheese. O.K., O.K., so your cholesterol can rise just reading the recipe. But it's a birthday! Isn't there something about birthday cake has no calories? In which case it wouldn't have cholesterol either.

I was at the New York Botanical Garden today, teaching a class in Patterns of Nature to an enthusiastic group of students. Why bubbles are spherical, cracking patterns in mud, differences between a spiral and a helix, Fibonacci numbers and fractal geometry, and lots more. After class, on my way out of the building I stopped to admire the shadow pattern of the elegantly clipped trees.

We had a wonderful summer, back in 1973. Back then, over 30 years ago, which puts it back in another century, Paul was working in Holland. The children and I went over for the summer, accompanied by a dachshund and two cats. I had rabies certificates for the animals, countersigned by the state veterinarian of Connecticut, where we were then living. My parents would stay in our house while we were away. Since my mother believed that dull knives were safer than sharp ones, I took my kitchen knives with me. We also brought necessary imports for other people in the company who were also working abroad: blue jeans, solution for contact lenses, disposable diapers, and (most embarrassing) Thomas's English muffins and Velveeta cheese.

Upon landing at Schiphol Airport and going to clear customs, it turned out that the rabies certificate did not stipulate whether it was the killed or attenuated form of the vaccine which had been used. Civilized, the airport officials telephoned a veterinarian in Leiderdorp where we would be living. When he said that was not a problem we were waved through.

Paul had reserved a Volkswagen Microbus. What we got was a Simca. Two adults, two children, two large wooden animal crates with a cat in each, the dog and her crate, suitcases, boxes . . . Leiderdorp was just far enough from the airport that one trip was all Paul would make. If it didn't fit, it would be abandoned. Somehow or another, everything fit and away we went.

We had rented a very nice house in a Dutch neighborhood. There was the street, a house, a backyard, the garage, an alley, then mirror image of garage, yard, house, and the next street. One day our son found a tortoise wandering down the alley. Its owner was later found. "Not to worry." our neighbor in the next house said. "I have a friend with TWO tortoises he wants to give away." We added tortoises to the menagerie.

I had a client back in Connecticut, whose home greenhouse I took care of. They gave me money to buy flower bulbs. A Dutch friend took me to the Van Eeden Bros. offices, spoke to them in Dutch, and next thing I knew I was buying bulbs wholesale. Seven and a half kilos worth.

Another day I took a bus (great public transportation in Holland) to a nursery where I bought 20 rhododendrons. They were small and if memory serves, they'd have been in 2 quart pots. And over the course of the summer other plants sort of adhered to me.

Summer wound down and it was time to go home. I had the airline notify the Agriculture Inspection Station at Kennedy Airport that someone was arriving on thus and such a flight with plants and an import permit. I washed plants clean of soil. The bulb company delivered a large box of bulbs. We said goodbye to friends and headed to the airport.

Plants, dog, cats, and chattel goods went into the cargo hold, the tortoises travelled in the cabin with us. Long flight. We arrived at Kennedy Airport. The rest of the passengers streamed away to customs. I found a largish wheeled cargo dolly, stacked it up it animal crates and went in search of Public Health. By now the Connecticut veterinarian had sent me a "proper" rabies certificate so dog and cats were checked off. "How big are the tortoises?" I was asked. I waved my hands, closer and further apart, only to be told "The little one is O.K. but the bigger one is illegal." I whipped out the card I had gotten from the United States embassy in Paris, which noted that there was no restriction on the importation of tortoises so long as they were in good health. (I wasn't quite sure what that meant, if you just sort of rapped on their shell and asked how they were feeling that day or what.)The public health official sighed, checked off "dog, two cats, two tortoises" and let us through.

I raced back to where Paul and the children were standing, surrounded by suitcases and boxes. The other passengers were significantly fewer in number. Paul had, however, written "and family" on his landing card so they wouldn't let him leave without us.

Unloading the animals I tossed box of bulbs, another of rhododendrons, the third one of assorted / miscellaneous plants onto the trolley and went off to the Agriculture Inspection Station. "Mrs. Glattstein, how nice to see you. Mr. Hidalgo [agent in charge, and a delightful man to deal with] told us you were coming. You have a phytosanitary certificate for the bulbs so we don't even need to see them. Let's look at the rhododendrons . . . They're diseased!" "No they're not." I said. "It was a hard winter. They have some tip burn, that's all." And the rhododendrons were allowed in. The miscellaneous plants were a slow matter: "What's this plant? How do you spell its name?" Finger sliding down the page, stopping, reading, "This one is O.K. What's this plant? How do you spell its name?"

Finally we get to customs. I'd bought a small green Delft vase at Die Porceleyne Fleiss, a piece of Wedgewood on a weekend in London (the same weekend I bought cyclamen tubers from Colonel Mars in Haselmere, Surrey while the rest of the family went to Buckingham Palace), we had some Grand Marnier Cordon Jaune (lemon flavored, lovely stuff, only ever found it in Holland) and various and sundry other bits and bobs.

So we finally arrive at customs. The landing card, somewhat dog-eared and a bit grimy and stamped with official stamps from Public Health and Agriculture, not much room remaining on which to write, is handed over to the woman agent. Looking at us she asks, "Are you a biology student?" To which my husband snarls back, "No, she's insane!"

That was over 30 years ago, and we're still happily married. Other things have changed though. It was very different then. I cannot image what would be involved to try and fly with a dog and two cats today. I doubt I'd have been able to bring the larger tortoise in to the country. A cordial reception at Agriculture? Probably not. Nor would tip-burn suffice as an explanation of why the rhododendron leaves were showing damage. And a box of miscellaneous plants - well, what do you think?

We had a wonderful summer, back in 1973.

The driveway did get plowed yesterday. It took Dave eight tries: backing clear across the street, revving the engine on his full size pickup and charging up the driveway until all four wheels lost traction, spinning clots of snow into the air, then backing down to try it again. Once, just for luck, he tried backing up the driveway. Didn't work any better. Persistence pays off though, and he did make it up the slope, around the curve in front of my tool shed, and all the way to the top.

Unfair. But then, who said life was fair. Wednesday afternoon had temperature of 74° Fahrenheit. I spent a couple of hours in the garden, picking up sticks and clipping damaged leaves and flowers from my hellebores. "Early Purple" was the most severely damaged, with all leaves completely brown and flower buds similarly scorched.

And H. foetidus was completely undamaged. I find this somewhat surprising, as this is the tallest growing of my hellebores, hence exposed to the brunt of the single digit temperatures that followed milder than normal conditions earlier in winter.

I mentioned this to Cole Burrell, a good friend, hellebore maven, and co-author of the hellebore book, who lives in Virginia. He had the same experience with his hellebores (though his were trimmed back in January.) Cole mentioned that he never cuts back Helleborus niger leaves, as this species responds very poorly. Fortunately I had left the foliage on my plants alone. In Hellebores: A Comprehensive Guide, published by Timber Press in 2006, co-authored by C. Colston Burrell and Judith Knott Tyler, mention is made that "Repeated bitter cold may compromise or obliterate the flower display, but this is rare." The book is aptly named since it is indeed comprehensive, and beautifully illustrated with photographs by Cole and Richard Tyler. It is an authoritative, very readable work that lucidly covers hellebores in the wild, how to grow them, using hellebores in the garden, interspecific hybrids and hybrid Lenten rose, breeding programs, and more. A useful work for those of us enamoured of this elegant genus, so perfect for the woodland garden.

But I digress. I started off to talk about the local, current weather. Winter started up again yesterday. Snow, sleet, a touch more snow, more sleet hissing down with icy spicules bouncing up off the window sills. Final score: airport cancellations and delays, highway traffic averaging around 35 miles per hour, and about 3 1/2 inches of crunchy stuff adhering to our driveway, stuck on so that cannot be plowed.

Forget Dolly the sheep. Long before scientists in their laboratories were duplicating sheep and afghan hounds and racing mules, gardeners were multiplying their plants using bits and pieces to make a whole. Asexual propagation gives uniform results, plants identical to each other since the genetic recombination of seed production is not involved.

Take a piece of a plant and convince it to make the missing bits. Understand this doesn't work in a uniform manner for every and all plants. But it works often enough, and is easy enough, that thrifty gardeners play along. Take a piece of a root and convince it to make a shoot. Conversely, take a shoot and encourage it to make roots.

Some points to consider for herbaceous plants: shoot cuttings are best when you choose non-flowering shoots. If only flowering shoots are available, remove the flower buds. A shoot in active growth roots more readily than a mature shoot or one entering dormancy. Roots form most readily at a node, that portion of a stem where leaves arise. The internode, or space between the nodes, does not readily form roots. And, since when you start off there are no roots, it is difficult for the shoot to support lots of leaves.

Once upon a time, long ago and far away - that's how all good folk tales begin. Not a fairy tale, but factual now . . . When I was just setting foot down the garden path there were several books which were seminal in my journey as a gardener. One of these was Elizabeth Lawrence's "The Little Bulbs, A Tale of Two Gardens." I have a copy of the original, 1957 edition, published by Criterion Books, New York. The preface begins: "This is a tale of two gardens: mine and Mr. Krippendorf's. Mine is a small city back yard laid out in flower beds and gravel walks, with a scrap of pine woods in the background . . ."

When Larry and I were discussing where we might go in my free time in Charlotte he casually said, "Would you like to see Elizabeth Lawrence's garden? I could call Lindie and I'm sure she'd be happy to have you visit." Would I? Hardly a question. More like a pilgrimage to hallowed ground.

Some background: Born in 1904, Elizabeth Lawrence was the first woman to graduate in landscape architecture at North Carolina State University. In 1948 she moved from Raleigh to Charlotte, North Carolina, where on a modest 70 foot by 225 foot lot with a small woodland at the back of the property she built a charming cottage and began making a formally designed garden. Five intersecting gravel paths outline four casual, informally mixed borders. The garden is still filled with a significant number of Lawrence's own plants, with as much as 60% continuing to prosper. A preeminent figure in the region’s horticultural history, early on Lawrence recognized that horticultural literature of the day (based as it was on traditional English practices transplanted to the eastern United States) did not relate to that of the Southeast. Accordingly, she set out to grow a diversity of plants in her garden and thus learn about them in the hot and humid summers and moderate climate of Charlotte. The plants would teach her, be her instructors. An excellent student, Lawrence kept meticulous records. She wrote numerous newspaper columns and authored several books detailing her experiences, sharing the information so carefully gathered. Lawrence lived here for 35 years until, in 1984 and in poor health, she sold the property and moved to Maryland where she died in 1985. In 1986 the property was purchased by its current owner, Mary Lindeman "Lindie" Wilson. Recognizing the significance of the property, Wilson (an accomplished gardener herself) has sensitively maintained the integrity of Lawrence’s garden.

And in an update after looking at the images I'd sent to him Jim wrote: "Seventeen Sisters" is probably as right as anything else: it seems to mean any daffodil or rose that has more flowers than you'd expect. Seriously, when people name Seventeen Sisters in reference to a daffodil, they're usually talking about Grand Primo or one of its several look-alike kin. And while I see enough of these various old clones to be leery of pronouncing anything as definitely Grand Primo, that's exactly what I think your picture shows."

Jim did come through for me, with the following information: "And the yellow, my dear, is a Campernelle! Of course you're right that it's a jonquil hybrid -- albeit an ancient hybrid that occurred in the wild -- and perhaps the most frequently encountered daffodil in rural parts of the Deep South. Campernelles are what Southerners usually mean to describe when they speak of "jonquils". Like Grand Primo, it's not so common up here [Raleigh-Durham area], but I became a daffodil geek largely because of the Campernelle and the way it glows in the sun!"

Looking first in my vintage copy of The Daffodil Handbook, edited by George S. Lee, Jr., and published in 1966 I find Narcissus × odorus, the Campernelle Jonquil, a cross between N. pseudonarcissus and N. jonquilla, recorded by Clusius in 1595. The Royal Horticultural Society's Manual of Bulbs, published in 1995, reverses the parentage thusly: N. jonquilla × N. pseudonarcissus. The first named is the seed parent, the second named contributes the pollen. Further, the Manual of Bulbs notes that it is very fragrant, of garden origin and is naturalized in southern Europe.

There are plans underway to preserve the Elizabeth Lawrence House and Garden. Already designated as a historic site by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Landmarks Commission, it has further been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Long-term management and care will be overseen by the Garden Conservancy . The two fold objectives are firstly, to use the property as a living horticultural laboratory. This will involve preserving and maintaining the landscape as it was designed by Elizabeth Lawrence, featuring many of the plants she grew, evaluated, and wrote about. This will not be a static, artificially frozen moment in time situation. The garden will also continue to function as a living laboratory, with new plants to be grown, evaluated, and thus identifying plants appropriate for the southern garden.

The second goal is the creation of a resource center incorporating a library and offering programing for visitors who come to visit.

Elizabeth Lawrence wrote several books, among which are A Southern Garden; The Little Bulbs: A Tale of Two Gardens; Gardens in Winter; A Rock Garden in the South, and others. There is a biography about her life, a book of her correspondence with Katherine Whiteside, and several collections of her newspaper columns. Most recent is Beautiful at All Seasons, edited by Ann L. Armstrong and Lindie Wilson, published by Duke University Press in 2007. Here, the columns are arranged by topic rather than chronologically: perennials and annuals; bulbs, corms, and tubers; trees and shrubs, etc. I confess, with my flight delayed for longer than the time in the air between Charlotte and Newark, I happily read the diversity of topics and observations, as fresh and relevant today as when they were written. A pleasant conclusion to a delightful visit.

Looks sort of like California, doesn't it. Only I'm still in Charlotte, where these windmill palms, Trachycarpus fortunei, have been growing for 25 years or so. While it would be inaccurate to call them invasive they're obviously happy and at home. Skip over a house or two and the neighbors have palm trees in their dooryard plantings too. I noticed some fair-sized seedlings, so I'll speculate that in the neighborhood these are pass-along plants, volunteers that get shared between gardeners..

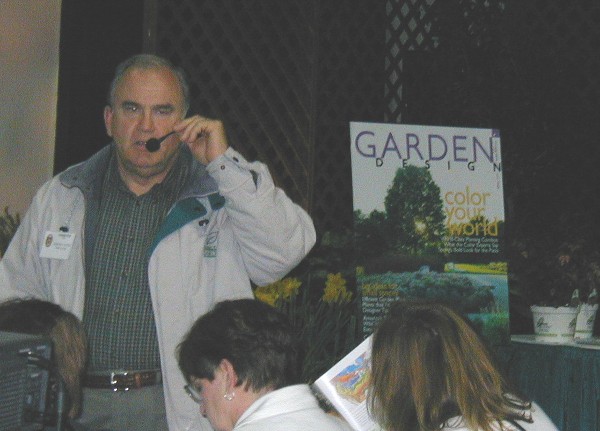

Today's my work-day. After all, I'm here at the Southern Spring Home and Garden Show at the behest of Garden Design magazine for their Living in Luxury Day, presenting a selection of the 2007 Way Hot One Hundred new plants. The day started off with a live radio show hosted by David Blankenburg. A great time just doing what gardeners do best - talking gardening. We did take some call-in questions too.

After our stroll through the greenhouse with its extensive delights we strolled over to the garden, filled with delights of its own: camellias in bloom, magnolias in flower, and one of the largest Edgworthia papyrifera I've ever had the pleasure of seeing, it's fuzz-covered white flower clusters centered with yellow. Masses of hellebores in drifts and sweeps, clustering along the banks of a stream, scattered in clumps hither and yon. A pleasant garden with gentle gradient, comfortable paths on which to stroll and converse with one another.

Heavy rain overnight, followed by moderate (for New Jersey) temperatures as I left at mid-morning for Newark Liberty Airport and a flight to Charlotte, North Carolina for the Southern Spring Home and Garden Show. Two hours in the air and wonder of wonders, I arrived into Spring: shirt-sleeve weather, daffodils in bloom, likewise cherry trees and camellias. Just lovely. Larry Mellichamp, a friend of more than 20 years standing, met me at the airport. A professor of botany and director of the UNC Charlotte Botanical Gardens, Larry made this the first stop of our garden-hopping tour.

Particularly noted for the McMillan Orchid Greenhouse, this is one of the finest collections to be found at any academic or public institution in America. There are thousands of specimens from all over the world, ranging from the very tiniest tropical orchids to a plant of the largest orchid species known. The collection heavily emphasizes species, as well as many outstanding modern and traditional hybrids. Exceptionally lovely as orchids are, these have a practical purpose too, being used for teaching and display. Several have won awards from the American Orchid Society. Should you wish to visit, the McMillan Orchid Greenhouse is open Monday through Saturday, from 10:00 .am. to 3:00 p.m. Visitors are welcome, and tours can be arranged by appointment.

This greenhouse is quite house-like, with separate rooms, one of which focuses on culinary mild temperate and tropical plants. Of course, Larry admits, many of these are not especially attractive. So while there is a vanilla orchid plant, it is the "hook" that allows the inclusion of more ornamental orchids. Fig is likewise on display, along with showier relatives.

filled with Crocus 'Advance' and Hyacinthus 'Splendid Cornelia'

provides a marvellous intimation of spring,

even temporarily placed on the icy snow over the picnic table.

with large brown patches on any leaves that were not flat on the ground and somewhat covered by fallen tree leaves.

I suspect that the upper or cuticle layer of the leaves had separated from the tissue beneath it.

I asked for a look at the horticulture department's greenhouses

where I saw this wonderfully attractive tricolor zonal pelargonium.

My address to the audience of 200+ attendees was Consider the Leaf: Foliage in Garden Design.

What better laignappe could I ask for than some cutting to bring home with me.

and another with stronger yellow markings and pink flowers. I asked for both.

What cuttings need is a damp yet aerated medium. 50 / 50 sand and peat moss is traditional.

I had been sent a sample of a gel pack rooting system and decided to give it a try.

four mallet cuttings, so called because the single node and individual growing point resembles that tool.

At the far right is a heap of stripped off leaves, to be discarded.

And in the background is an unprepared shoot, similar to the one from which I made 5 cuttings.

The mallet cuttings were put into a plastic market pac filled with damp perlite.

At this time of year - pre-Spring - I expect rooting to occur reasonably promptly.

With a little more effort, it is also suitable for some woody plants such as azaleas and camellias.

Charlotte, North Carolina

has happily made several large colonies in the front yard,

despite the occasional distribution of excess plants.

Seed is rarely produced, but the bulbs make numerous offsets.

Whorls of leaves clothe the lower stem while tendril-like leaves above the flowers

hold fast to brush where they grow in their native eastern China habitat.

so available that they'd be discarded after forcing into early bloom.

They are, unfortunately, much less readily available today.

Originally planted by Miss Lawrence, these survive but have not made offsets

or self-sown. Larry suggested some delicate work with a camel hair brush

to encourage better / more reliable pollination.

About early white trumpet daffodils she wrote:

"The upright buds begin to dip as they open into

the lovely swan's neck curve that is characteristic of many white trumpets."

Later on the same page she describes Narcissus cernuus "or moschatus if you follow the experts,

but I am not sure that I do. . . The flower is smaller that that of the Silver Bells, and the stem shorter,

but the neck is bent in the same way. This is sometimes called the silver swan's neck daffodil.

It usually blooms the very first days of March."

They flutter a leaf, suggesting I guess again. So it is with this charming tazetta daffodil.

The group consensus (me, Lindie, and Larry) was Seventeen Sisters,

a popular heirloom variety in the South and Southeast. I mentioned this quandary to my friend

Cole Burrell who lives in Virginia. He handed off to Jim Sherwood, who currently resides

in Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina but with gardening experience in Alabama. Jim suggests,

"My first guess would be Grand Primo. I don't see that much here, but in the deep south

it's very common in old neighborhoods, and Elizabeth Lawrence certainly corresponded with folks

who would have access to these. The timing sounds right, and also that they'd look all white by now.

I also have Polly's Pearl blooming now -- much like Grand Primo but even less yellow in the cup.

And there are paperwhites that will sometimes wait this late, depending on weather

(but mine bloomed ages ago, in January)."

under the big window that looks out upon the garden.

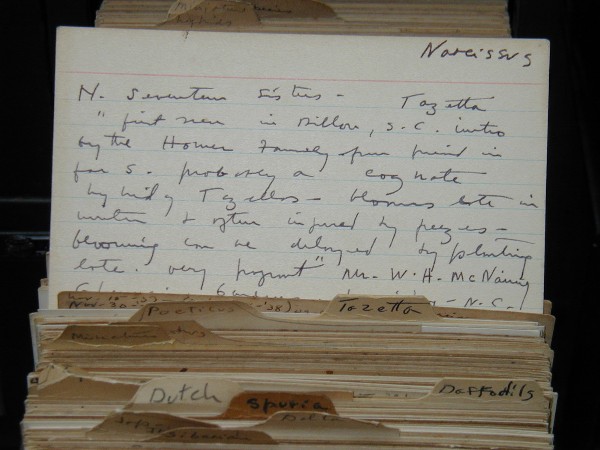

What temerity. I tug open the daffodil drawer

curious to see what notes she had made about Seventeen Sisters.

Fingers crossed, perhaps Jim will have a good suggestion.

Looking at the rounded leaves I'll go with jonquilla, or a jonquilla hybrid.

The leaves are so beautiful it wouldn't matter if it never flowered.

They'll open like a candle flame, maroon in color.

This is one of the species native to the southeastern United States.

Not that gardeners ever truly have time to sit around in a leisurely manner.

spoke about the most beautiful gardens in America, discussing hardscaping, water features, plantings, and more.

could it be the ribbons he won for his orchid entries?

I especially like the collective display of the Seagrove Potters Co-operative.

A demonstration potter's studio, and items for sale.

Dang, but those airline overhead compartments seem to shrink every time I think about them.

on a Summer Classics garden sofa.

Weatherproof from wicker-like furniture to soft poly fabric cushions

the company provided the furniture for the Garden Design space.

accenting the yellow-throated flowers.

which Larry tells me is pronounced "see lodge eye knee".

Larry is noted for his work hybridizing pitcher plants, sarracenia species native to the Green Swamp of North Carolina.

Small wonder then, that this tropical pitcher plant would hold his attention.

Some of these tropical insectivorous plants are truly carnivorous, with pitchers large enough wherein a mouse might drown.

This sturdy cacao pod filling with its beans, is the progenitor of rich and delectable desserts.

before flowering plants evolved have a dinosaur to keep them company.

He looks rather carnivorous, definitely not a peaceful vegan critter, don't you think?