By now it's a tradition, and not just for me. Many people find the The New York Botanical Garden's annual festival of G-gauge trains tootling through the conservatory a welcome part of their winter holiday rituals.

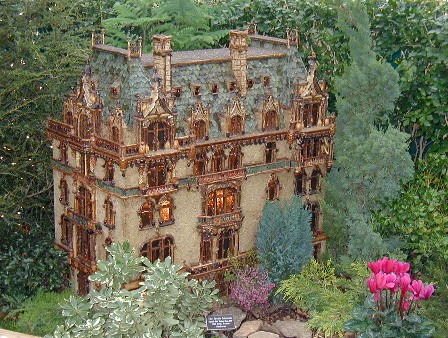

The first display opened in 1991. There was a time while the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory was undergoing renovations (1993 and 1994, to be exact) when the show was held outdoors on the lawn in front of the beaux arts museum building. There was something magical about standing outside in a snowy landscape, icicles forming at the edges of the waterfall, and watching the trains huff and puff through the minature landscape. Now firmly located inside the conservatory, the event is no less fascinating, with new buildings added every year. Replicas of actual New York City buildings and bridges crafted from twigs and pods, branches, leaves, and cones, acorns and seeds, the landscape appeals to children of all ages, gardener and non-gardener alike.

Creativity is in the details, and the imagination. Designed and built by Paul Busse and his aptly named team at Applied Imagination of Cincinnati, Ohio, the bridges and buildings create a fanciful kingdom. A hollow log is a tunnel. Window shutters are made from sycamore bark while a house is thatched with fungus collected from fallen logs. Another has an oak bark door with cherry bark hinges, that opens with the turn of an acorn handle. Walls crafted of white poplar leaves, window panes of elm bark - these materials are not found in a local building supply yard. Rather, Paul says, you have to gather them when and where you find them throughout the year. It takes 10 days to set up the display of bridges, buildings, tracks and trains, as well as the landscaping the accompanies each set piece.

The New York Botanical Garden's holiday train show is closes just after New Year's. Closed on Mondays, the grounds are open Tuesday through Sunday, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with free grounds admission all day Wednesday, and until noon on Saturday.

As gardeners, we are but a link in a chain of those who grow plants for their beauty. Created four centuries and a decade ago, today snow dusts the ground of the Clusius garden, as seasons turn and the garden rests in winter. Plants we take for granted today were, at its inception, exciting introductions from abroad.

Leiden, in the Netherlands, is a city of great historical importance for many reasons, and especially for gardeners. The Hortus Academicus was founded in 1587, making it the earliest scientific garden in Europe. Its first director, Carolus Clusius, was appointed in a professor of botany at the university in 1594. Coming from Vienna, where he had studied the plants of Austro-Hungary founded a Hortus medicus, or physic garden in 1573, this was a major transition for him. Sixty-six years old, crippled from a fall, one of his conditions for acceptance of the position was that the Curatores of the University grant him the use of a garden then temorarily being used as a Hortus medicus. He wanted this space to cultivate his bulbs, plants for which he had great fondness. Tulips were introduced into the North of Europe by Clusius, who raised the original plants in 1573, from seed sent to him by his friend Olgier Gislain de Busbecq, ambassador from Emperor Ferdinand I to the court of Suleiman the Magnificent. Clusius grew another new introduction - in 1594 he grew tuberose, Polianthes tuberosa, from Mexico. He was among the first to cultivate Lilium martagon, soon after its introduction into cultivation in 1596, calling it Lelieken van Cavarien.

Today's recreation of the Clusius garden. across a small canal from the botanic garden itself, and behind a tall brick wall with a wooden door, has been laid out according to a plan and a plant list that was drawn up in 1594 by Clusius himself. It contains many of the medicinal plants studied by the 16th and 17th century's students of pharmacology and medicine. A small wooden fence surrounds specimens of Clusius' bulbs (the choicest of which, in his day, were stolen by theirves who crept into the garden by night.)

And in another four centuries . . .

We lived in the Midwood section of Brooklyn when I was a child, a neighborhood of large houses on tree-lined streets. East 17th Street had a mall down the center, with trees and shrubs. A summer-time stroll down shady streets was a pleasant exercise. When autumn came, however, everybody crossed over at the corner. That house had a large, mature ginkgo tree. A female ginkgo tree. In autumn it was loaded with lovely inch to inch and a half round fruits, pinkish yellow with an orangish blush. Ginkgo may be popular as a nutritional supplement said to improve memory. If you've ever smelled the fruit of a ginkgo I guarantee you need no help in rememboring it. The stench is remarkably pungent, with overtones of vomit. The flesh is a vesicant, and can blister the skin of your hands if touched.

Ancient indeed, ginkgo has been around for 150 million years. The unique fan shaped leaves turn a wonderful bright yellow in autumn, and all of them fall off simultaneously in less than a day when the weather turns cold. Adaptable, this ancient of days grows anywhere from Massachusetts to California, Minnesota to Florida, reaching anywhere from 50 to 80 feet tall. Just be careful to specify a male tree at the nursery, and you'll be secure in its fruitless nature. Like hollies and certain other trees and shrubs, ginkgo is dioecious, meaning that male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. If you want to sample the nutmeats: gather the fruits while wearing plastic gloves. Wash free of pulp in a bucket of water. Briefly microwave the nuts, which explode if cooked more than a few seconds. The green nutmeats have a somewhat gelatinous texture and mild taste. I've been told that only a few should be eaten at any one time, or dizziness and heart palpitations can occur.

Autumn is a time when many trees and shrubs (perennials too) expend a burst of energy into fruit production, genetic recombination for the next generation. Birds and beasts alike depend on this source of food. Turkeys and deer adore acorns, as do squirrels and blue jays. Unlike the soft berries of summer, migrating birds such as robins carbo-load on autumn fruits before migrating south for the winter. A flock of robins can strip a flowering dogwood, Cornus florida, in less than a day. Other trees, such as American holly, Ilex opaca, retain their fruits until winter's end, thus providing a vital food source for returning robins.

The days when people would a-nutting go, gathering hickory nuts and black walnuts, are mostly in abeyance. Though in the South and Texas pecans are often gathered from trees that grow on a family's land, then shelled by hand or taken to a commercial facility.

Today the fruits of autumn are appreciated more for their aesthetic values than as a food source for winter's want. Too, that means tthat even fruits we would not eat are admirable. Consider Oriental photinia, Photinia villosa. Not especially common, this large, multi-stemmed shrub has dainty clusters of white flowers in May to June. It is the bright red fruits that ripen in October, persisting into winter that provide a more ornamental aspect.

Crabapples are extolled as flowering trees for the garden. Available in sizes from a 10-foot tall lollipop (Malus sargentii) to more stately, 25-foot tall specimens, no less an athority than Michael Dirr refers to flowering crabapples as " . . . the dominant spring-flowering tree in the northern tier of states, where cherries, dogwoods, and magnolias are often relegated to second-class status." Many have an upright habit of growth. 'Red Jade', an older cultivar has an attractive weeping habit. The deep pink to red flower buds open to inch and a half flowers, with the most profuse bloom often an alternate-year event. Looking at the surfit of brilliant, 1/2 inch diameter fruit, clearly 2005 was a good year.

Crabapples want full sun. Oriental photinia will clearly accept shade. Another uncommon shrub for sun to lightly shaded woodland gardens is Sapphireberry, Symplocus paniculata. At Willowwood it grows along the woodland path that follows the little stream. It's clear that several self-sown individuals are adding themselves to the community of Japanese maples and stewartias. Native to the Himalays, China, and Japan, you might be excused for passing it by in spring and summer. Fall color isn't of much interest either. But when the small fruits ripen in September, their turquoise-blue color will stop you in your tracks. Birds are said to appreciate the fruit, so having a Sapphireberry in your garden offers the best opportunity to enjoy its great appeal in autumn, as well as attracting birds.

Located at 300 Longview Road in Chester Township, New Jersey, Willowwood Arboretum is the sort of special place you almost hate to mention. If other people learn about it, they too would return again and again. Once the private estate of two Quaker brothers, their parents and sister came to visit and never left, also fell in love with the place, just moved in and stayed. Quiet, never crowded, there are times when I feel that I have the Willowwood all to myself, to appreciate the ever-changing cycle of the seasons there: winter, when snow deliniates the bare branches, in spring as tender green leaves unfurl, summer, and now autumn. There are superb magnolias, Japanese maples, crabapples, stewartias, and more. And autumn's vivid colors and fruitful bounty are amply well displayed.

There's much to enjoy at Willowwood: the large fields of tall grasses, excellent site for the many bluebird houses that are here; crabapples on the "back" side of the stream; and the modestly proportioned flower garden with carefully deliniated cloister-styled flower beds filled with an exuberant and playful mix of flowers, bulbs, and annuals. Perhaps my favorite though, is the walk more-or-less along the woodland stream. There's no doubt that the area is cared for, but it is not regimented. There's room for self-sown seedlings (but then, who wouldn't welcome seedling stewartias!) Groundcovers, a fallen tree with its roots shrieking to the daylight, that once were darkly kept buried in the earth. The path begins quite near the house. A pocket handkerchief-size lawn, a Japanese lantern and a pool of water with stepping stones across its narrowed outlet to lead you under the sheltering branches of tulip poplars, canopy for the smaller trees that shelter beneath them.

When early European settlers in North America sent home reports of astonishingly bright autumn foliage color as trees and shrubs turned from green to glowing tones of orange, red, scarlet, and purple, they were disbelieved. Fabulous, in the sense of almost unbelievable, incredible, purely imaginary, a fabrication. Given the right conditions of warm sunny days and cool nights, plants that have the potential to do so manufacture anthocyanins in their leaves, thus producing these autumn bonfire hues. It cannot happen if nights are mild, days are overcast, or if suitable plants are shaded. Had the European settlers instead been Japanese, there would not have been any doubts. For suitable conditions are commonplace in Japan, as in the northeastern United States and parts of eastern Canada.

Japanese celebrate momijigari each fall, the splendid color change provided by their smaller maples such as Japanese maple, Acer palmatum and its numerous cultivars, and full-moon maple, Acer shirasawanun. Whether the Japanese maple has leaves that are summer green or summer purple, in autumn they mostly turn to glowing, luminous red (a few turn to buttery yellow.) The New York Botanical Garden celebrates this seasonal event with a Momijigari display in the Enid Haupt Conservatory's hardy waterlily courtyard, from October 13th through November 19th. Large Japanese maples, along with cryptomeria as an evergreen contrast, bamboo in pots, and drifts of perennials. Wonderful bonsai provided by the Yama Ki Bonsai Society of Stamford, Connecticut are also on display.

I went to see this year's display on November 2nd, accompanied by my students in GAR230, History and Traditions of the Japanese Garden. What a wonderful time we had! The day was comfortably crisp, with a small zephyr of a breeze to rustle the leaves of the maple trees, and the pots of sere brown grasses actually growing in the pool.

I'm not certain if, while not on display, the trees are grown elsewhere on the garden's grounds or if new trees are provided each year. Certain elements do reappear: the entrance gate into the courtyard, a bamboo lattice fence, the large pots of bamboo that have a bright green, turf-like groundcover of Scotch moss are welcome reminders of previous visits. As well, there is a little, open, garden house. It has a roof, a back wall as high as the roof, and a side wall that leaves a gap from upper edge to the roofline. When sitting on its built-in bench with an open view before you, open to the side, and breezes blowing through, there is a sense of shelter but little, if any feeling of separation from the garden.

In addition to the momijigari garden there were two pots of thousand-blossom chrysanthemums over by the visitors' center entrance. Keep this in mind - chrysanthemums are raised from cuttings. A small shoot is started in the spring, grown on until it flowers in the fall, then rests through the winter until a new little division is taken the following spring to begin the cycle anew. A chrysanthemum may be pinched at the tip. It branches. The new shoots are pinched, and branch, pinched again, and so on. Rather than a chrysanthemum that would have a few flowers, a many-splendored thing is grown. Patience is required, and care. Once a certain point is reached the single stem that comes up from ground becomes fragile, top-heavy with all the multiple shoots. A sturdy metal framework is necessary to hold each shoot in the desired relationship to the others, protecting it from mishaps. A small collar supports each individual flower. And then . . .

photo credit Carla Teune

Located in the parking area, small wonder that nearby spaces are left empty!