Back in the last century, when Donald Lacey of Rutgers University was trying to select a day for the Summer Open House at Rutgers Gardens, he studied the metrological records and found that the day least likely to have rain was the last Saturday in July. The record was unblemished this year, with moderate temperatures, softly overcast skies, and sufficient gentle breezes to let us all feel comfortable. "The Power of the Flower" was obvious, as the lovingly tended beds in the Donald. B. Lacey Display Gardens were at their peak of bloom. Rutgers Gardens thrives on the efforts of volunteers, student interns, and members of the community. It supports itself largely through the spring and fall plant sales in May and October, and the smaller summer event in July. More than 40 Adopt-a-Plot gardeners and volunteers plant, weed, and tend the flower beds, herb plots, and vegetable gardens that comprise the gardens. There are two large beds that display the 2005 All-America Selections annuals, another one especially devoted to flowers that are suitable for dried bouquets, two beds of herbs, and a couple of beds for perennials. Twenty-five plots of mix and match annuals in brilliant colors - lots of zinnias and marigolds, cleome and petunias, black millet and coleus, and lots, lots more.Twenty plots for vegetables, and even a butterfly garden too. As well as familiar flowers there are cutting edge, too new to even be called new introductions. That's thanks to Ira Grasgreen of Eason Horticultural Services who trials some of next year's introductions at Rutgers Gardens before they even reach garden centers and nurseries.

Today you can see mature shrubs and trees such as Dr. Joseph Orton's hybrid hollies, cornelian cherry, Cornus mas and C. officinalis, and useful examples of hedging plants for the befuddled homeowner attempting to choose among the various options. As well, there are choice specimen trees and shrubs from bottlebrush buckeye, Aesculus parviflora, blooming now with its fluffy white spikes to the exotic franklinia Franklinia alatamaha, found only a few times in the American Southeast and never seen in the wild since 1803, on Saturday opening the first of its pristine, camellia-like white flowers, to Chinese jujube, Ziziphus jujuba, from temperate Asia. Rutgers Gardens almost vanished. The land was to be sold to a developer. Coordinated protests from New Jersey garden clubs, Rutgers University students, and other concerned citizens staved off the bulldozers. The land was not sold, but the gardens were not funded. The extension service decided the display gardens of annuals were too costly to maintain. That's where the plant sales and Adopt-a-Plot volunteers keep the gardens thriving. What's more, there's not even an admission fee. The gardens are open to the public for their enjoyment and edification.

The plant sales are a splendid mix of familiar and unusual plants. Saturday's choices included a couple of choice hosta cultivars, lovely narrow-leaved lungwort, to tender agaves (at better than eBay prices); the beautiful intense magenta flowered little hardy orchid from Japan and China, Bletilla striata; at least five different kinds of cannas and even more vatieties of colocasia.

There were hydrangeas and leucothoe, dwarf forsythia and mahonia, magnolias and franklinias. I had barely stepped inside the sales area, ready to offer assistance to anyone with a question - "No. I'm afraid Synadenium, also known as milk bush, is not hardy. You'll have to bring it in for the winter." - when I spotted five of them, in bud and thus ready to flower later this summer. Priced at a modest $30 each, how could I resist? I chose one - somehow it is always easier to select something for someone else rather than myself. It took at least 5 minutes of dithering before I knew which one wanted to come home with me. The next five hours went by quickly, as people happily chose just the right plant for their gardens. "Gardens" is an elastic term, as at least two people told me of their extensive collection of plants in pots. And I don't mean pelargoniums. Try everything from a tri-color beech to a wide range of tender perennials such as colocasias and banannas. There were others though, who preferred to enjoy the beauty of the gardens.

By the time midafternoon rolled around I was feeling a little tired. It had been a busy time, and "home" sounded better and better.

So I loaded my franklinia, a pretty chaste tree, Vitex agnus-castus 'Shoal Creek' with terminal spikes of blue flowers, and a funky little Colocasia fallux, barely ankle-high with a silvery center to its mid-green leaves and clearly a spreading habit, in the car and drove homeward.

I intended to plant the franklinia after dinner. Unfortunately when I started to clear the area I quickly found there was a nest of yellow jackets in the ground right where I wanted to the little tree to go. They nailed me five times before I was far enough up the driveway that they gave up the pursuit. After putting benadryl ointment on the stings and taking an antihistamine I went back down Magnolia Way and from a goodly distance sprayed the nest opening. On Sunday morning I tiptoed close to the site, clutching a rake with which to see what was what. But overnight a skunk must have come waddling along and had a midnight snack, for there was a small pit and no wasps. A bit more weeding / clearing, digging with the addition of compost and composted woodchips, and Ben Franklin's tree, descendant of those brought out in John Bartram's saddlebags, was made welcome at BelleWood Gardens.

Some summers are better than others, but the image of butterflies that stays in my mind is a visit to a prairie restoration in Gray Summit, Missouri. Arriving mid-morning on an August day, literally clouds of butterflies lifted from the flowers : swallowtails, fritillaries, and monarch butterflies that were nectaring on liatris, Liatris spicata and an assortment of yellow daisies. These large butterflies with orange wings spotted and striped with black, yellow wings with black stripes, black wings dotted with orange and blue along the trailing edge were truly like flowers on the wing.

Butterflies pollinate, caterpillars dine on plants. If we want butterflies we have to accept their caterpillars. Some thrive on plants we don't care about. Others, such as the black- and yellow-spotted green caterpillars that metamorphose into black swallowtail butterflies feed on parsley, carrots, dill and other members of the Umbelliferae family. Monarchs, both as caterpillars and adult butterflies, utilize milkweeds such as orange-flowered butterfly weed, Ascelpias tuberosa, and the mauve flowered common milkweed, A. syriaca. These plants contain glycosides, which accumulate in the caterpillars and remain in the adults, sufficient to violently nauseate any bird that eats one. Tough for the monarch butterfly that gets eaten but good for the species as a whole. The birds are quickly conditioned to never eat another butterfly that even looks like a monarch. Viceroys and admirals use protective mimicry for a look-alike appearance that offers protection even though their caterpillars feed on the leaves of trees in the willow family in the case of admirals, and viceroy caterpillars feed on violets.

This seems a quiet summer for butterflies in my garden. A few cabbage whites, some black swallowtails

an occasional tiger swallowtail like this beauty nectaring on an appropriately named butterfly bush, Buddleja alternifolia,

or a hummingbird-like clearwing sphinx moth. But there is still some summertime remaining.

Proudly billing itself as the largest green industry summer event on the east coast, PANTS is a three day trade show featuring plants, pots, tools and trinkets, and more. Hosted by the Pennsylvania Landscape and Nursery Association, this trade show is a "must attend" event for nursery and garden center operators large and small, both local and at a distance. There are tree growers offering everything from specimen size to liners - conifers, fruit trees, shade and flowering trees. Evergreen and flowering shrubs, and roses. Perennials, annuals, and bedding plants. Pots from plastic to fiberbord, plain terra cotta to colorful glazes and stuff to fill them - soil mixes, additives, spent mushroom compost, peat moss, fertilizers, and more. Hardwood, pine bark and cedar mulches. Edgers, pavers, stone and bricks. Biological pest controls to powerful chemicals to control insect pests and diseases. Tree spades of a size to move instant landscape specimens, automated state-of-the-art potting equiptment, motorized wheelbarrows, and garden carts that move by muscle power. Poly houses and greenhouse supplies such as shade cloth, potting benches, fans, and automated systems all the way from watering, fertilizing and heating controls up to computers and computer programs for nurseries. As you would expect, there are numerous exhibitors from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut, as well as Delaware and Virginia. As well, there are several from Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, Alabama, and Florida, in addition to a surprising number from Oregon.

The Fort Washington Expo Center in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania is enormous. I cannot tell you exactly how many vendors are there but definitely over a thousand, and five hours is not enough time to visit them all. Some people methodically go up one aisle and down the next. I tend to check out the 100 pages or so listing exhibitors by catagory, and then try to get to the booths that interest me the most (especially those of friends.) Along the way I pick up pounds and pounds of literature, samples, and trinkets. Some people come with luggage wheelies to haul the accumulated material around with them.

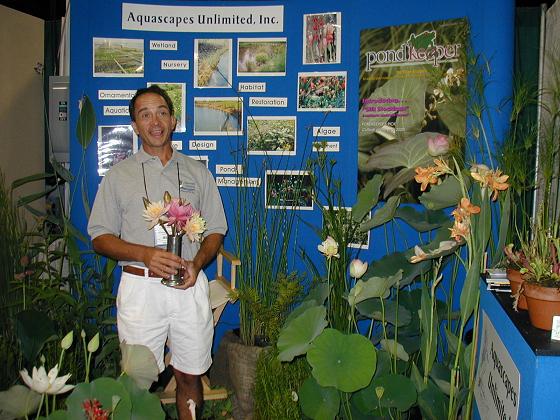

There were 33 vendors of water gardening and pond supplies - plants, stone, pumps, koi, and more. Every year a must-see booth for me is that of Aquascapes Unlimited, Inc., a wholesale water plant nursery in Pippersville, PA. Telephone 215 / 766-8151. Specializing in insectivorous plants, Randy Heffner also produces water lilies, lotus, and shallow water plants both hardy and tender. He selected and developed 'Silk Stockings', a lovely form of our native arrowhead, Sagittaria latifolia, with very dark foliage. Attractive throughout the growing season, it's a knockout when in bloom as the white flowers stand out against the black leaves.

While the trade show guide's cross reference lumps bedding plants, annuals, perennials and ground covers together, it has a separate category for native plants with 32 entries. Of course this includes trees and shrubs as well as native perennials. My consistent favorite is North Creek Nurseries, Inc, located in Landenburg, PA. They propagate a goodly range of native grasses and perennials. I find their super-size plugs especially useful. Steve Castorani was at their booth, and we had an interesting and informative chat about what's coming up with their production and promotion of native plants. A keen eye for selected forms of familiar plants and production of less common ones (do you know and / or grow Maryland pinkroot, Spigelia marilandica? That's the red firecracker-like plant on the left in the picture.)

The nursery is interested in what others are selecting and growing. They now offer several of the unusual color forms of prairie coneflower, Echinacea purpurea, with deliciously soft yellow and warm sunset hues.

In my trawling up and down the aisles in a disorganized zig-zag fashion I am occasionally stopped in my tracks by a display. J. P. Bartlett Co. Inc. specializes in pelargoniums, hybridizing and selecting their own zonal geraniums, as well as producing a few ivy geraniums and other summer bedding plants, selling plugs and bench run stock. In 2005 their plants are on display in trial gardens operated by Penn State University, University of Tennessee, University of Georgia, North Carolina State University, and Michigan State University.

Another astonishing thing about PANTS is that enormous as the show is, with two huge exhibit spaces criss-crossed by aisles and cross-aisles, with people wandering hither and thither - you still manage to come across friends you didn't even know would be there. This merry smile belongs to my dear friend Stephanie Cohen. She's always happy, but especially so right now because the day lily shown on this catalog is named for her - it's 'Stephanie Returns', a Happy Ever Appster® cultivar selected by Daryl Apps and offered by Centerton Nursery Incorporated. Located in Bridgeton, New Jersey, the company offers branded plants such as Happy Ever Appster® day lilies, BlewLabel® ornamental grasses and Summer Jazz Seasonals™ (tender perennials and seasonals).

An interesting day that would have been enjoyable in any event, all the more so for the sultry weather - rather like walking into hot exhaust from some enormous machine. The front that came through around 5:00 p.m., ripping leaves, twigs and small branches out of trees as it dropped a little less than a half inch of rain also saw the temperatures drop nearly 20 degrees in just minutes. Now to get back into the garden!

There was a dribble of rain overnight, then tremendously noisy thunderstorms in the morning. Lightning bolt and thunderclap sometimes simultaneously, meaning the electrical discharge was too close to call. And the net result? Today's weather has reverted to form. From the brilliant sunshine and low humidity of the weekend we've gone straight back to hazy, hot, and humid. Though the sunshine is strong enough to cast shadows, the sky has faded to gray and distant objects are blurry. I was going to Clinton to do some shopping in mid-afternoon, driving down Route 513, passing some crop fields that were planted to sorghum last year. I've been driving by these fields on at least a weekly basis. Filled with a vague "something green" - not corn, not soybeans, suddenly they were enormous fields of sunshine. Sunflowers, tens of thousands of sunflowers, filling the field and stretching on into the indefinite distance.

Sunflowers are members of the Compositae, or daisy family. Each flower is actually composed of many individual flowers: the central disc has one type, and the ray flowers at the disc's perimeter are another. Cheery and bright, many sunflowers, Helianthus species and cultivars are popular in gardens. There are ornamental cultivars of the common sunflower, Helianthus annuus, such as 'Italian White', with pale primrose yellow flowers on 5 foot tall plants, and 'Teddy Bear' with shaggy, fully double bright yellow flowers on 3 foot tall plants. 'Russian Giant' grows as much as 10 or 11 feet tall, with heads 10 inches or more in diameter. Several cultivars are also popular as cut flowers.

These acres of sunflowers are clearly crop fields, not ornamental gardens. Sunflowers are grown commercially for their seed, and not just for bird food. People like the seeds too.Native to North America and Mexico, sunflowers were gathered from wild-growing plants as an indigenous food by indians of the American West, and cultivated by the Hopis. Adaptable, annual sunflower may be grown in Mexico where it takes 7 months from sowing seed to harvest, and equally well in Canada where the cycle is completed in just 4 months. This explains why sunflowers are an important crop plant in Russia, where the cold climate limits what plants can be grown. In fact, world-wide, sunflowers are second only to soybeans among plants grown for oil. Cultivars such as 'Peredovik', 'Progress', and 'Rostov' yield a high grade oil.

Sunflowers are a major crop in North Dakota. I've always wanted to go there when the flowers were in bloom, to see them stretching away in the distance. And today, just 4 miles from home, I saw sunflowers carpeting the earth.

I go out of state for corn. Of course that means simply crossing the Delaware River, turning left once I'm over the bridge and driving a few hundred yards (if that much) to Lewis' Farm Stand on the Pennsylvania side of the river.

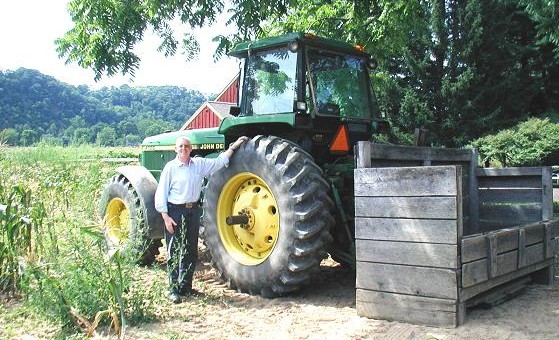

They generally have a few oddments too. Today it was a couple of bunches of beets and perhaps a dozen eggplants. First and foremost though, primarily they sell corn, There's a good-sized container type trailer with a sun shade in front of it, covering a table and two large wooden bins for corn on the cob, one for yellow and the other for white. Prices are moderate, six ears for $2.25. Certainly that's more than the supermarkets charge, but it is like the difference between Dick Nagy's blueberries and peaches and fruit bought in the grocery store. Fresh, and local. Doesn't get much better unless you grow it yourself. Lewis' corn is picked the morning of the day you buy it, and driven from the field to the stand with a huge green tractor, wheels taller than I am.

Corn is a highly domesticated crop. The original wild plants of teosinte were native to Mexico. The oldest known remains of the two-rowed wild grass ancestor of modern corn was found in the Valley of Tehuacan, and has been dated as 7,000 years old. The earliest corn cob, complete with husk-like casing, is 5,000 years old. Think of how important the crop became, first traded into what is now the American West where it gained mythic stature with the Hopi and Navaho tribes. It is part of our folk legends too, with the tale of Squanto introducing this new food to the Mayflower immigrants. For by the time they arrived from Europe, corn had also reached the Atlantic shore. The Iroquois revered corn, calling it one of the three sisters (beans and pumpkins were the other two.) They had an excellent technique for growing the plants in hills, a system so successful that they were able to produce large harvests with extra grain to store against winter scarcity. Different from the row system used in Europe for grain crops such as wheat, the new settlers disapproved of the strange and different style of gardening. They would not try the hill system that was suggested for the new crop, insisting on keeping their familiar row and furrow method.

There are five types of corn:

With its thick husk wrapping the kernel-filled cob, corn depends on us to disperse its seed, for a cob that falls to the ground cannot release its seeds, which are unable to germinate. Wind pollinated, corn has male flowers at the top of the cornstalk, and receptive female flowers lower on the plant. In the home garden corn is better planted in a block rather than a row, for better distribution of pollen. There is one strand of silk for each kernel on the cob, as the silk is the remnant pollen tube from flower to corn kernel. Modern varieties of corn generally produce two ears per plant. Corn is a hungry crop, needing ample nitrogen for vigorous growth. White corn is the sweetest I think, while yellow corn has a more intense corn flavor. I like yellow corn for cooked dishes such as corn fritters or corn pudding, and prefer white corn for eating fresh.

Farmers need to protect their crops from all sorts of pests - birds, especially crows, eat the seeds while deer eat the young plants, and raccoons will smash a stand of corn flat to the ground in their eagerness to dine. As well, there is a fungal disease, corn smut, Ustilago maydis, which grossly swells and blackens the kernels, which have an unusual silver color. Its Mexican name is huitlacoche, (pronounced something like "wheat la coach hay") and it is considered a delicacy. Last year an infected ear showed up in my friends John and Carol's vegetable garden. Look at this picture.

Can you understand why Carol told John to toss it into the burning barrel for later incineration? I told her to salvage it, ASAP. That night we had a huitlacoche feast of corn soup, a chicken dish, and a recipe I developed for mako shark steak, using tomato (another food gift from Central America), red onion, and huitlacoche. Look at the size of those kernels, nearly as big as the tomato, and the black center of the sliced pieces. Raw, it has a slightly bitter taste. Interestingly, each dish had its own unique flavor.

Huitlacoche is sometimes available canned, but my cookbooks suggest that it isn't very good. You'll have to grow your own corn and hope that the fungus infects it. John and Carol are increasing the odds in their favor - they planted corn in the same corner of their garden, having left the remains of the infected plants as a mulch over the winter. They promise to let me know if this uncommon fungus will again show up in their little plot of 24 plants of corn.

There are gardeners who cultivate what I perceive as collections - an array of hostas displayed next to each other, differing only in size and variation of leaf color: all green, with a white edge, white center, golden edge or center. Useful for comparing this cultivar with that one, but hardly the sort of effect that makes you stop in your tracks and go "Wow!" when you come upon them. The same underwhelming display can be achieved with daylilies, a genus which also has a plethora of cultivars. No, my preference is for a garden that uses plants in combination, playing this leaf against that one, these flowers contrasted with those. Which is not to say that I do not succumb to honest horticultural lust for a particular hosta or daylily.

Several years ago I was coming home from the Millersville, Pennsylvania native plant conference early in June. There is a large garden center right next to the road, and even on the correct side as I pass by. Trees, shrubs, perennials, annuals, pots and tools and fertilizers and more. By now I barely have to twitch the steeling wheel. My car knows how to swerve into nurseries and garden centers. Given the conference focus you'd think I had been innoculated against "foreign" plants. Not hardly. When I saw this superb daylily with its elegant dark flowers I was tempted. And tempted, I succumbed.

The label disappeared years ago, but I am reasonably confident of the name. I adore the deep maroon flowers, set off by a glowing yellow throat. The color is so intense that dead-heading spent flowers stains my hands with the same burgundy color, one that even scrubbing with a powdered cleanser only fade but does not remove. Though each flower lasts but a single day, the scape is nicely branched and there is a good bud count to keep the plant in flower for a reasonable length of time. It is growing in the tropical bed under my study window, home to Musa basjoo, the hardy banana, as well as tender and tropical perennials such as the dark leaved canna just visible in the upper right-hand corner of the image.

I appreciate them in daylight for at dusk they begin to fade into invisibility, their dark hues blending with the night.

Yesterday I saw a young boy running along the sidewalk towards the library and commented to his mother that one has to be young to run in this weather. Paul described it perfectly. As I mentioned in a previous post, he called the weather obnoxious.

Everyone agrees that they cannot recall another summer with as long a stretch of high humidity and uncomfortable temperatures. There is so much moisture in the air that even the sunlight is dimmed, like light from a dusty bulb. Temperatures hover in the high 80s Fahrenheit, which does not sound so bad. However, when coupled with the humidity it makes even a slow stroll down the driveway to pick up the mail a sweaty exercise. And conditions can be lethal. Jerry has a good-sized stock pond that was dug in one of the sheep pastures many years ago. Three-quarters of an acre in size, it is stocked with blue gills and bass. Yesterday when we went to take a look we found a large number of dead blue gills along the shores. I believe that these small fish tend to inhabit the shallows. Warm water holds less oxygen, and the fish suffocated. The bass are probably hanging out in the deeper, cooler water at the pond's center, where it is 14 feet deep.

There's a concept I've seen on some British forums such as Creative Living for the 21st Century. They suggest living a fulfilling life, creatively downsizing your life, and enjoying each day by, among other things, eating seasonally. If you are not growing it yourself, they counsel purchasing local fruits and vegetables with low mileage attached to it. This is a concept that has always appealed to me. Apples are all well and good, but there comes a point when I crave summer fruits: cherries, peaches, plums and berries. Goodness knows where the supermarkets get them. Peaches from Georgia, grapes from Chile. I'm fortunate that Dick and Carol Nagy and their superb orchard are only a few miles from my home. With all the heat and rain the trees and bushes are bearing profusely, helped along by Dick's expert care. Farm chores and subsequent harvest do not wait on the weather - when they're ripe, the crops must be picked. So Dick was out in the heat and humidity picking blueberries, deliciously sweet little red Metheny plums, and the first of the local peaches that I've been hungering for. When he called I was out the door and into my car like a shot. Here's a picture of what I brought home.

I have several large containers at the bottom of the driveway, created from sawn apart plastic barrels. (Three others were used for rain barrels behind my toolshed.) Since I was not going to make water gardens in them, in addition to cutting them apart for me Paul made the necessary drainage holes. They have worked out much better than anticipated, other than one incident with a snow plow (well, they are white and there was snow on the ground) and another with a careless truck driver backing up. What did surprise me was the survival of some lilies year after year, winter after winter.

Lilium 'La Reve' was acquired from a big box store, planted as an "annual" but has refused to succumb to winter. Instead the bulbs have multiplied. Typical of the Asiatic hybrids, they bloom every July on 2- to 2 1/2-foot stems with upward-facing flowers. A pleasant reward for walking down the driveway to retrieve the mail, and a welcome return home from an outing.

This has to be one of the longest spells of obnoxious summer weather. It's hot, and its humid. I remember a summer down in Orange, Texas near the Lousiana state line a number of years ago. I asked one of the local residents what they did before air conditioning. He drawled, "Honey, they walked slow, and they talked slow." That's it in a nutshell. The humidity is so high, the air so saturated with moisture this morning that the outside of some windows were fogged with condensation.

We've had a fair amount of rain this summer. Yesterday was again rather warm and quite humid, gray skies with intermittent rain. Paul and I walked up to the Forest Deck with Pol and Huguette, to show it off to them. And on the way back down what did I espy growing right along the edge of the path where they've never been before but golden chanterelles, the first of the season. Quickly (as the rain was starting up again) I picked enough to fill both men's hands, and a few more for me to carry.

I'd already defrosted a package of corn with chanterelles that I'd frozen last summer, to make a side dish for our dinner. Why not a mushroom feast with sauteed chanterelles to go on our steak grilled under the infrared broiler in the oven. So that's what I did, and a succulent delight it was too. Should you want to try it, here's the casserole recipe.

Thaw two cups of corn with chanterelles.

Place in a pre-heated 400° Fahrenheit oven for 20 minutes.

There are even more chanterelles today, big ones and little ones, cropping up along the side of the path, on the other side of the path, even in the path. They're along the infrequently running drainage ditch that disappears into a culvert under the driveway. I can tell that this is going to be the Year of the Chanterelles. For lunch I made an omlet (locally bought eggs from free-range hens) filled with chanterelles. Delicious!

August Update: The dry weather has resulted in a pathetic harvest of wild mushrooms. A season that had begun in such a promising manner quickly petered out. First the chanterelles dried to a tan, suede-like consistency, and then never even re-appeared. Spoiled we were, by the two previous years generous harvests.

A lovely word, entomophilus. It refers to plants that have their flowers pollinated by insects. What it actually means: entomo refers to insects. And Philius, in classical mythology, is an epithet of Zeus, meaning friendly. And of course those plants that rely on butterflies and bees for pollination love their insect partners and act friendly towards them. The name of the game is reproduction, and flowers are a form of advertising.

The earliest plants arose before there were insects. They used the wind to distribute their pollen, and the wind blows for free.Wind-pollinated genera include conifers and grasses. Of course this is a haphazzard means of distribution: it is the luck of the draw if wind-bourne pollen transfers from one plant to another of the same genus and species. Should pollen from a pine arrive on a spruce its not very helpful to either individual. Plants tend to up the odds of success by growing in a community of their peers. There are other plants in a community, and this can give one plant a bad rap that actually belongs to a different one.

Goldenrods are often accused of causing hay fever. Ragweed is a frequent neighbor of goldenrod. Its inconspicuous, wind-pollenated flowers are easily overlooked. Once you recognize that flowers are intended to attract insects it is a simple step to appreciate they will have sticky pollen. Why have flowers if the wind might bear the pollen away before its transport arrives? In hay fever season, when your eyes itch and your nose runs sunny yellow, insect-pollinated goldenrod is not the culprit.

Flowers offer payback to their insect guests in the form of pollen and nectar. They invite them in with bright colors and appealing fragrances. The sweet smell of old-fashioned roses works for bees. The dull reddish-purple spathe and carrion stench of dragon arum, Dracunculus vulgaris, successfully lures the flies that pollinate its flowering spadix. Single flowers make better landing platforms. A simple black-eyed Susan has better potential than a fully double flower. Besides, it is often the sexual parts, stamens for example, that are altered into petal-like form. Not only more difficult for a bee or butterfly to settle down, there's less, perhaps even no pollen to make it worthwhile. Single flowers have better potential for attracting butterflies and bees.

Many flowers have markings, called bee guides, that direct the insects to the pollen-bearing portion of the plants. Think of the yellow blotch at the base of the falls on Siberian iris. These are like MacDonald's golden arches visible over the treetops along the highway as you drive along, announcing that there's food to be had. Insects see some different wavelenghts of light than we do, further into the ultraviolet. Under a black light, flowers that appear evenly colored to human eyes may display a bee guide that's more obvious to their pollinating insects.

Clever advertising pays off. Look closely at the flower of Queen Anne's lace, Daucus carota. In reality, the white flower is composed of numerous tiny white flowers, increasing the odds for successful pollination. Near the center of all of these clustered flower is a single deep purple speck. To a cruising insect it looks like someone's already settled in for a snack, making the landing strip more appealing. If there were lots of little specks it would be like a diner with most of the booths already filled, so crowded that you'd rather not wait for a seat. Clever, these flowering plants.

So for a garden that's popular with butterflies choose entomophilus plants. Select those with single flowers with colorful petals and a sweet fragrance. And enjoy their lovely flowers and the flutterby visitors that pollinate them.

I heard cicadas shrilling in the trees this morning, that sustained whirring sound that comes with summer. As I sat, having breakfast out on the deck behind the house, a bowl of yogurt with local blueberries from Dick Nagy, thinking that today would be another hot and humid one (scattered thunderstorms are predicted for the afternoon) it seemed early for them to be emerging from the Stygian darkness of their underground nymph-hood. Periodical cicadas spend years as burrowing, root-feeding nymphs. They leave the soil by night. Once partway up a tree the nymph grabs firm hold of the bark. Its shell splits down the back and the adult emerges, leaving the ghost-like remnant of its juvenile self behind. Once they've mated and laid their eggs in twigs of deciduous trees the adults soon die. The hatchlings fall to the ground and burrow down to feed on the roots of trees and shrubs. Some cicadas mature every year, but mass emergence events occur at long intervals of 13 to 17 years. This is not such a year but those that have reached maturity loudly announce their presence.

This is a year for massive numbers of Japanese beetles. An accidental, unfortunate importation into the United States, the beetles were first discovered in 1916, in Riverton, New Jersey. Currently the beetles have spread from Ontario and Nova Scotia south to Georgia and westward to Tennessee and Missouri, with local outbreaks reported in California. The adults are actually quite lovely, small scarab-like beetles of metallic green and bronze. The difficulty is that all they seem to do is eat a wide variety of leaves: trees both ornamental and fruit-bearing, shrubs, vegetables, herbaceous perennials, and annuals. Leaves are skeletonized, and yucky wet poop disfigures the remnants. They eat flowers too. Nothing so disgusting as finding a pair of them having at it in the heart of a rose. That's the adults. The grubs feed on plant roots, especially lawn and turf grasses.

I remember when I was a child spending my summers in Brookfield, Connecticut my aunt would pay a nominal sum for my efforts at knocking Japanese beetles into a can of water with a film of kerosene. Fast forward to modern times. Desperate gardeners put up pheromone traps designed to attract sex-crazed male beetles with the scent of artificial hormones. (The traps also contain a floral lure that attracts both sexes.) Once they enter, beetles fall into a collection bag for disposal. This year I've heard of traps filling up within hours. While I have no idea how much an individual Japanese beetle weighs, it cannot be very much. My friend Jerry attracted a pound of them in just 4 hours! He's collected a total of 3 1/2 or 4 pounds by now, and comments that removing that quantity from the environs of his garden has to have some effect in reducing not only the damage but also next year's population. Would that it were so. Personally, I think the traps are fabulously effective at attracting beetles. And I have quite enough of them, thank you very much. Now, if I could convince my neighbors to install the traps . . .

Update - Wednesday, 20 July: Jerry is still collecting Japanese beetles. It has slowed down somewhat, to a kilo a day, two days in a row. That's 2.2 pounds of Japanese beetles. So, I wondered, how many beetles is that? Jerry has some very precise equipment for tissue culturing plants, including a digital scale housed in an enclosed case. He collected 13 Japanese beetles and selected 10 representative specimens. Next, he placed a small paper dish on the scale and reset it to zero. Then we weighed the beetles. Are you ready for this? Ten Japanese beetles weigh just over 9/10ths of a gram. (We only bothered to note the reading out to three decimal places.) A kilogram is a thousand grams. So near enough, a pound of Japanese beetles contains 4,500 beetles. That's a lot of beetles, to say the least! Now back to my original entry.

August Update - Sunday, 20 August: The blasted bugs are still around. They ate the silk off Jerry's block of 'Silver Queen' corn, intended for the second harvest. No silk means the ears, wind pollinated, are filling very poorly. He had been dumping the beetles into a plastic bag with a spoonful or two of gasoline, to kill them. Then he'd strain off the gasoline to reuse it for the next pheromone-trap collection of beetles. He's switched to microwaving them.

In my garden the Japanese beetles ate the flowers on my bottlebrush buckeye, Aesculus parviflora, gnawed on my hardy banana, Musa basjoo, ate the tops off masses of touch-me-not, Impatiens capensis down along Magnolia Way, and, cruelest blow, I actually found a couple in the second flower to open on my new franklinia, Franklinia alatamaha. Wicked critters.

Back to the original entry.

Milky spore disease is touted as a natural means of control, a bacteria that attacks the grubs. I have not found it to be especially useful in my region. First, it must be applied over a large area of lawn. Next, it takes a couple of years before an effective population of bacteria is available to control the grubs. Lastly, if we have a cold winter with little snow cover, the bacteria are wiped out. Much more effective are hunter-killer beneficial nematodes. The drawback here is that you must make yearly applications. The nematodes are sold as a dirty-looking square of spongy window screening in a large container. There's a use-by date, so make sure it has not expired. Nematodes, miniscule transparent worm-like critters, are quickly killed by low humidity and sunshine, and cool temperatures. Mid- to late summer is the best time to make an application. On a damp, overcast, lightly rainy day fill the jug with water. Agitate throughly, and apply the nematodes with a hose end sprayer or a watering can. The nematodes burrow through the soil. When they find a grub they burrow into it through body openings such as mouth or breathing spiracles, and kill it. In addition to Japanese beetle grubs, beneficial nematodes attack other grubs such as June bug, cutworms, and more.

Early this morning while the beetles were still somewhat sluggish I knocked them into a container of soapy water. It seems to stun them. Some sink to the bottom while others kick feeble-y, and blow tiny little bubbles. When I'd had enough of the patrol duty I flushed them down the toilet. Highly unlikely they'll emerge from the septic system.

The rains have been adequate this summer, even plentiful at times. Trees are green with a full, dense canopy. Lawns are green too, and require frequent mowing, even now, in July. They came again, after midnight, a steady, drenching, soaking rain. Not a monsoon nor a tropical deluge, just a constant delivery at a tenth of an inch per hour. By morning the rain gauge held better than half an inch. Emptied, it was ready for more. And more it received. The pace picked up and in 7 hours the rainstorm delivered an additional 1.8 inches. That's a lot of water, nearly 2.5 inches. With an inch of rain a collection area such as roof feeding into a rain barrel, that amount of rain provides 64 gallons for every 100 square feet. So this storm delivered the equivalent of approximately a gallon and a half of water for every square foot of ground. Like I said, that's a lot of water.

Zephyranthes comes from the Greek, zephyros meaning "the west wind" and anthos, "a flower." Native to the southeastern United States, South America, and the West Indies, these little bulbs are mostly tender, or at best, semi-hardy. They sleep through the dry spells, then hurl forth their leaves and crocus-like flowers within days of a drenching rain. A watering can will serve as proxy, but a rainstorm is better. Habranthus robustus is the most frequently available species, even showing up in packages at the big box stores here in the Tri-State region.

Update: Tuesday, 12 July 2005

Another pot full of rain lilies has burst into bloom. This dainty sweetling is Habranthus martinez. A friend in England sent me a few bulbs several years ago. With minimal attention they have multiplied nicely. Last Friday's rainstorm pushed their "on" switch. Five days from dormancy to bloom - now that's what I call instant gratification!

It is easy to become quite fond of these charming bulbs. There are several species and cultivars, with white to cream, yellow, coppery, or pink to rose colored flowers. Yucca Do Nursery, in Texas, is an excellent source, offering two dozen species and cultivars of zephyranthes and habranthus. The bulbs are small enough that a handful may be planted in a medium size pot. I prefer one with more shallow, bowl-like proportions, to suit the modest size of the growing plants. Their cultivation is simple, for they are not fussy about the care they need: now dry, now wet, and always kept free from frost. Keep the potted bulbs on the dry side when dormant. Provide just a sprinkle of water every three or four weeks to keep them from dehydration. But they must be kept dry, or the rain will not trigger them into growth. So you have this pot of bare-looking dirt. When summer is truly here and a pleasant steady rain descends from the heavens simply set the pot outdoors. Quickly, unbelievable fast, the flowers and narrow dark green leaves appear. With summer rains come the flowers of the west wind, blown in by the storm.

A number of years ago, in fact, in the previous century, my friend Carla Teune of the Leyden Botanic Garden in The Netherlands accompanied Roy Lancaster on an expedition to Mt. Omei in China. She sent me seed of several plants, including an unidentified arisaema. When it flowered a few years later, it was identified as A. fargesii by H. Lincoln Foster. In "Travels in China, A Plantsman's Paradise" (published by the Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, in 1989) Roy Lancaster gives me credit: "and the first flowering that I heard about occurred in the United States in the garden of Judy Glattstein of Connecticut, in 1985. Her plant produced a hooded flower exhibiting a striking combination of white, green and blackish-purple stripes. The spathe curved forward and downward at the tip ending in a tail-like point, while the spadix was poker like, greenish, and contained within the spathe."

This morning I took a slow stroll up the path alongside the drainage creek and saw three plants of Arisaema fargesii in full impressive leaf, and in bloom. It has been barely a week, perhaps less, since I was on this path. I didn't overlook them because they are small and dainty. They simply were not there. The summer arisaema may be late to appear, but they certainly hurl themselves into growth once they decide the time is right. Think of the tripartite leaf as having a T shape, with a huge central leaflet. On one plant the central leaflet measures 11 inches long by 10.5 inches across the widest portion. The two horizontal leaflets measure 17 inches from the tip of one to the tip of the other. The other plants are much the same size. In their book "The Genus Arisaema" (published by A. R. G. Gantner Verlag KG, Ruggell / Lichtenstein) and writing about section Franchetiana, Guy and Liliane Gusman note that "The eophyll is a simple blade and further, leaves remain simple for many years, first developing some kind of lobes, often just outlined, eventually becoming fully separated as the tuber matures."

A. fargesii has a striking spathe, boldly marked in contrasting stripes of deep purplish red and white. This species has some kinship to A. candidissimum in that both are in the section Franchetiana, all four species of which are native to western China.

Unfortunately, the peduncle (the pseudo "stem" which bears the spathe) is shorter than the petiole so the spathe is below the leaf, rather than at the same height as in A. candidissimum. While the dark markings make the spathe quite visible, some neck craning is necessary to get a clear view. Still, it is a striking plant well worth growing in the garden.

I went to visit Ellen today. Of course we did what gardeners always do when they visit each other. She showed me around her gardens, those made, those under way, and others that exist only as future options, potential ideas that may (or may not) reach reality as currently envisioned. Of course, Ellen has some advantages few other gardeners have, like a husband who has a bulldozer and a backhoe as his "big boy's toys" - and no aversion to using them for garden projects. So we walked around and looked at daylilies in splendid bloom, lots of thread-leaf coreopsis doing likewise, and various other daisy family perennials in flower or about to be. Like gardeners everywhere, Ellen has overflow plants in pots. Some are perennials she's propagated but has not decided where they'll find a home, and others are plants acquired but not yet planted. There was one group of potted plants that came from a swap meet. A man had come with black plastic garbage bags filled with assorted plants. Jumbled together and sans any labels, it was sort of like a lucky dip. What you got would be good, but you might not know what it was. Difficult for a gardener to resist this sort of situation.

There were two pots of a nice looking plant with apple green glossy leaves on upright stems. It looked like something I should recognize, but I could not recall its name. Not something I'm currently growing, not something I tried to grow and it died, but it sure looked like something I'd seen before. "Take one." Ellen said, "I have two pots and besides, there's a couple of plants in each pot." I didn't need much persuasion. In fact, from the way I'd been carrying on, "admire to acquire" was more like what I was doing. As we walked around some more, talking as we went, a memory tickled my mind. "Pollia," I said, "I think it is Pollia."

The memory comes from several years ago. I visited the National Arboretum as part of the garden tours when the Perennial Plant Association had its annual meeting in Crystal City, Virginia. In the Asian Valley Garden there were masses of Pollia japonica in bloom. It was difficult to photograph because the plants were growing in rather heavy shade. The 2- to 3-foot tall stems were crowned with numerous small white flowers in open clusters. Its Japanese name is yabu-myouga.

After lunch I looked for information about the plant in several reference books. I did find it in Jisaburo Ohwi's "Flora of Japan" (published in English by the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. in 1984) and also in W. George Schmid's "An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials" (published by Timber Press, Portland, Oregon in 2002.) Somewhat surprisingly, there was no mention of pollia in Ran Levy-Yamamori and Gerard Taaffe's "Garden Plants of Japan" (published by Timber Press, Portland, Oregon in 2004.) Schmid's excellent book contains both scientific information and practical gardening advice. He mentions that pollia is an invasive plant. I can understand that - the pot that Ellen gave me had sent questing roots out the drainage holes into the soil beneath, and I believe she's had it for less than 2 months.

Questing through the lower garden along Magnolia Way with pot in hand ("There, there, dear. I'll find somewhere to plant you.") I found a promising site behind some ferns and brunnera. The tangled mass of roots and rhizomes separated into 5 pieces. Once planted, I watered. Yes, yes, I know rain is forecast for the evening but I can almost hear the voice of my mentor, John Osborne, supervising me as I plant something in his Westport, Connecticut garden. "Is it raining on your head Glattstein? If it's not, then water." A goodly layer of mulch, some more water on top of the mulch, and the pollia is planted. Will it flower this year? I have my doubts. How rampageous will it be? Schmid says very vigorously rhizomatous and spreading, and it should be contained. Gardeners with ample gardens could, he notes, grow it in the open ground but a watchful eye should be kept on the colony's perimeter. Looking at the white rhizomes with a new branching here and a nubbin of a bud there, I can believe it. But we'll see. A thick colony could crowd out weeds. As long as it doesn't crowd out what I consider desirable neighbors for the pollia. Such as the daffodils I inadvertently disturbed, already with a good growth of roots in preparation for winter survival.

And, in the evening, it rained. Doesn't matter, I'm still glad I watered, and happy that the rains came too.

Summer is bounded by holidays. The equinox may be in June, but the sense is that it begins with Memorial Day, the last weekend in May. And ends with Labor Day, the first weekend of September. A convention, a tradition, an arbitrary set of boundaries for summery weather continues beyond the set point of September's first week. Between those two celebratory events lies the Glorious Fourth, Independence Day, the 4th of July. Parties planned in advance and spur of the moment get-togethers alike make the holiday weekend one long celebration, a time for picnics and parties and fireworks. Barbecues and cook-outs, hot dogs and hamburgers, potato salad and coleslaw, and cakes decorated to resemble the stars and stripes, the flag of the United States of America with a field of blueberries and red stripes of sliced strawberries arranged on white icing.

This year the weather and the festivities alike were glorious. From heat, humidity, and rain the weather was transformed to perfection: sunshine, gentle breezes that sent clean white clouds across the blue sky like laundry billowing on a line. The moderate temperatures providing weather appreciated all the more for the torrid stickiness that came before it, and warm enough for swimming,. We spent time with family, neighbors, and friends, with a casual dinner down the road on Saturday, a visit to our son-in-law's parents place on Lake Mohawk on Sunday, and a Jump in the Creek party here on the Nishisackawick on Monday.

Saturday I got in about 6 hours of weeding down along Magnolia Way. And discovered that apparently there is a nest of yellowjackets under the bench just across the drainage creek. Something to tell the pest control technician when he comes for his routine summer visit in August, sooner if they become more aggressive! A refreshing shower, and in the evening we brought our steaks over to John and Carol's house, along with some portabella mushrooms and eggplant to grill, and vanilla and chocolate ice cream for dessert. A pleasant time sitting, talking, eating and drinking. John grills a great steak, made his inimitable chips, and Carol had picked snap peas from her garden. We ate out on their terrace / patio by the light of a kerosene lantern and watched the first stars appear, with fireflies in mimicry over the lawn.

Sunday morning I started the string trimmer and cleared the wide, overgrown path from the front lawn down to the driveway, and trimmed back a narrow strip along one side of the driveway at its edge, from the lawn down to the mailbox. Then used the blower to clear the bits and pieces of debris, and caked seeds from the sycamores, drifted in along the driveway's edge. I even went up into the woods to the Forest Deck and cleared it of immature hickory nuts that are falling in the natural thinning process as the trees reduce the crop. A shower to rid myself of dirt and sweat and bits of seeds and stems caught in my hair, and it's time to drive to Sparta, New Jersey for the holiday dinner and get-together at our son-in-law's parents house. He, unfortunately is working, flying to Puerto Rico. But our daughter and two of her daughters are there, along with her brother-in-law, his wife, and their two children, plus Scotty, their amiable golden retriever. Along with other siblings, spouses, children, friends. It's a good thing Pol and Huguette have a lovely deck outside their house, with a lower deck large enough for the barbecue grill and a few people congregating around the grill-meister, plus a shaded lower terrace / patio area beneath the upper deck. The lawn slopes down to the water, with a four-square rustic fishing hut offering additional seating. It is a fishing hut, Huguette tells me, because that's where the fishing poles are kept. I look at the sturdy floor and roof of the small building, open at both sides and in the front save for an openwork cedar pole railing and just a bamboo screen at the back to offer more privacy. There's a table covered with a provencal patterned tablecloth and some casual, comfortable chairs. Surely more charming than fishing hut suggests. The dock is not huge but there's room for some chairs as I find out later in the evening. I brought a chicken liver pate as a pre-dinner appetizer. Here's the recipe in case you want to try it.

1 Granny Smith apple

1) Allow butter to soften to room temperature

There were tasty salads, not your usual tossed greens but things such as black bean with corn off the cob and diced mango. Grilled chicken breasts, steak, and boneless pork. Five desserts, from a flag cake to bumbleberry pie (that has several different kinds of berries) and a chocolate mousse cake. Ample time afterwards to sit, talk, and digest before the lowering sun provided us with a splendidly colorful sunset over the hills across the lake. And then - fireworks, with the best possible seats for viewing. I was among the group that took chairs down to the dock, while others watched from the fishing hut or the upper deck. That's the human contingent. Upset by the loud explosions, Scotty tried to wedge his portly fur-covered frame into a secure hidey hole in a bedroom. The fireworks were set off from a barge anchored a hundred yards or so out into the lake. A fabulous view of superb fireworks: huge golden sparkles silently drifting down like tentacles of an enormous jellyfish; quick, loud, flat BANG echoing across the lake as clouds of green, red, magnesium white sparkles expanded, then faded away to nothingness; twisting snakes of white light arcing up from the barge before exploding into colorful display. Clever people the Chinese, to have first invented gunpowder and then developed such a delightful use for it. Finally it's all over - fireworks, festivities, and party - time to go home.

But that was Sunday. Monday was the Glorious Fourth, and brought with it another day of fabulous weather and another great party. This one was at neighbors down the street, with people relaxing in a huge grassy field shaded by big trees, and the Nishisackawick running wide and shallow, enjoyed by kids and dogs. Pictures tell it all :

Dent corn, Zea mays indenata, is sometimes also called field corn, and is often used for feeding livestock, to make processed foods, or for industrial products.

Flint corn, Zea mays indurata, is commonly known as Indian corn. Kernels may be white, red, purple or blue. It is used for much the same purposes as dent corn.

With a soft, starchy kernel that is easily milled, Flour corn, Zea mays amylacea, is used for baked goods.

Pop corn, Zea mays everta, has a very hard shell on the outside, and a soft, starchy center. Popcorn is one of the oldest kinds of corn, with archeological evidence found in New Mexicothat dates back to 3600 B.C.

Sweet corn, Zea saccharata or Zea rugosa, is primarily eaten fresh off the cob. It can also be frozen or canned. Sweet corn contains more natural sugars than other types of corn, and it is seldom used for feed or flour.

Beat well two eggs.

Add 1 cup whole milk.

Add salt and black pepper to taste.

Toss corn and mushrooms with 2 Tablespoons of flour.

Combine mixtures and pour into a well-buttered oven-proof casserole dish.

Stir gently to better distribute corn kernnels.

Return to oven and bake for another 30 to 40 minutes, until the top is delicately laced golden brown.

shallots

1 lb. chicken livers

1/4 pound unsalted butter

1/4 cup Calvados

thyme, salt, black pepper

2) Peel, core, and cut apple into small dice

3) Dice 1/4 cup shallots

4) Sautée apple in 1 Tblsp butter over medium heat for about 6 minutes, stirring frequently, until somewhat softened

5) Add diced shallots to pan with 1 Tblsp butter

6) Sautée shallots together with apple for another 3 or 4 minutes, stirring frequently, until shallots are soft

7) Remove from pan into a bowl, wipe pan with a paper towel

8) Add 1 Tablsp butter to pan, together with half of the cleaned chicken livers

9) Sautée over medium high heat until chicken livers are browned outside and still pink inside

10) Remove from pan and repeat with remaining chicken livers

11) Return everything - first batch of chicken livers, apple and shallots to pan. Add Calvados. Heat, then set alight. Swirl pan, shaking gently, until flames begin to die down, then extinguish by putting a tight lid over pan.

12) Scrape everything into a food processor. Add 1 teaspoon fresh thyme or 1/2 teaspoon dried thyme, 1/2 teaspoon salt, freshly ground black pepper to taste.

13) Pulse until a smooth paste has formed. This takes only seconds, so pulse briefly, check the texture, repeat as necessary.

14) Scrape out of food processor into a Pyrex pie plate or other shallow non-metallic container. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 30 minutes or until cool but not refrigerator temperature.

15) Beat in remaining softened butter until completely combined.

16) Scrape into serving container and refrigerate until ready to serve.

5 July

Deinanthe bifida

15 July

Silphium connatum

22 July

Monarda fistulosa

7 July

Arisaema fargesii

15 July

Arisaema consanguineum