.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

Why are plants green? Chlorophyll, that which allows plants to obtain energy from sunlight, poweringthe process whereby plants synthesise carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water. Photosynthesis. Oh. That's not the question. Plants appear to be green because, to put it simply, their leaves (and stems) contain chloroplasts. Red and blue light is absorbed, green is reflected so we see their leaves as green.

Except when plants are not green. Saprophytes obtain their nutrients from dead or decaying matter. Mushrooms are saprophytes. There are others, such as beech drops and Indian pipes, ghostly white plants.

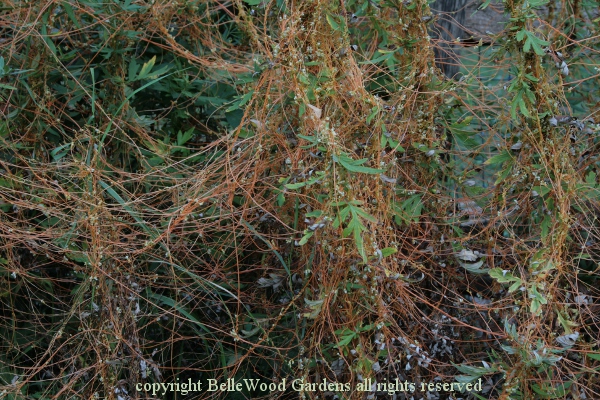

How about vampire plants? Something that gets its necessary nutrients not from sunlight, not from decaying matter, but by sucking the juices from green growing plants. Yes, there are actually vegetable vampire plants. Like dodder. Folk names include devil's guts, devil's hair, devil's ringlet, goldthread, hailweed, hairweed, hellbine, love vine, pull-down, strangleweed, angel hair, and witch's hair. Their seeds germinate in the soil, just like other plants. But within just a week or two the young dodder plant must grasp on to a nearby green plant. Its roots will wither away as it clings and climbs and sucks the juices from its host. At maturity dodder opens small, inconspicuous flowers which are pollinated, produce seed, and the cycle begins anew the next year. Perforce, now that I think about it, dodder must be an annual.

This is not something that's good for the host plant. See the difference in growth - green and vigorous on the right, stunted where the plants are caught in a net of dodder's orange threads on the left.

.

.

The haustoria penetrate the host plant, linking the two together.

What funky things plants do. But wait. There's more going on than you might think.

Information courtesy of a news release from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Virginia Tech described research by Jim Westwood, a professor of plant pathology, physiology, and weed science. He examined the relationship between dodder and two host plants. During their parasitic interaction, there is a transport of ribonucleic acid between the parasite and host. [Riboneucleic acid, or RNA, are large biological molecules that perform multiple vitally necessary roles in the coding, decoding, regulation, and expression of genes.] His new work expands on the scope of this exchange, examining the mRNA, or messenger RNA, which sends messages within cells telling them which actions to take. Heretofore it was thought that mRNA was very fragile and short-lived, so transferring it between species was unimaginable. But Westwood found that during this parasitic relationship, thousands upon thousands of mRNA molecules were being exchanged between both plants, creating this open dialogue between the species that allows them to freely communicate. Through this exchange, the parasitic plants may be dictating what the host plant should do, such as lowering its defenses so that the parasitic plant can more easily attack it.

Academic interest only? Hardly. Parasitic plants such as witchweed and broomrape are serious problems for legumes and other crops that help feed some of the poorest regions in Africa and elsewhere. This research throws open the door to a new arena of science that explores how plants communicate with each other on a molecular level. It also gives scientists new insight into ways to fight parasitic weeds that wreak havoc on food crops in these destitute parts of the world.

So if you happen to see a tangle of orange threads along the road or in a field or in your garden, now you know what it is. A small infestation can be managed by riping out the dodder and its host plants. Every time you see it and definitely before the dodder can flower. It took me several years to destroy the dodder that was vampirely attacking a patch of yellow dead nettle, Lamiastrum galeobdon by ripping out handfulls of the affected portions - stems and silver splotched leaves - until no dodder was left. And doing the same the next year, and the next, and the next. Fortunately it was a small patch in a visible location. No need to go out after dark with a flashlight and garlic. But what fascinating things plants do.

Back to Top

Back to August 2014